Editor's Note: Author Dan Sally originally posted this write up for his podcast, Middleweight Politics, on his website. It has been republished in its entirety with permission from the author. Photo Credit: Quick PS on Unsplash

Over the weekend, Senate negotiators released final language of a bill that would address the growing crisis at America’s southern border while also providing aid to Ukraine and Israel. This would be great news, if House Speaker Mike Johnson hadn’t announced the bill was dead on arrival before the bill had been written.

The situation at the US Border with Mexico became a core part of the Republican platform after Donald Trump made it the centerpiece of his campaign in 2016, which, oddly, was a time when illegal border crossings were at an all-time low. Now, in a case of a broken clock being right twice a day, border crossings have passed their historic high of 1.6 million in 2000 and increased 5X in the last 8 years.

While many on the left have pushed back on decreasing the flow of migrants across the border in recent years, the arrival of many of those same migrants to Democratic-dominated cities and polling showing the issue hurting Joe Biden appears to have brought them to the table.

So it puzzled many that, right when Democrats were ready to negotiate, their Republican colleagues began to pull back.

Many attribute the move as a reaction to Donald Trump’s public and private lobbying to kill the bill, implying Republicans would get a better deal if he were reelected. So the party that once claimed the border was on fire now appears to be ready to let it burn a little longer in the hopes a better fire truck arrives.

So, is the real problem at the border, or is it in Washington?

In the midst of the border crisis, Congress has been unable to address a growing fiscal crisis in the form of deficit spending, and a real ‘crisis’ crisis in the form of people lobbing missiles at each other in Ukraine and the Middle East.

So the real question doesn’t seem to be what’s the best way for Congress to solve problem X or Y, but how to get them back to being able to solve problems in the first place.

In looking at the last few decades of voting and electoral data, a trend becomes clear, as does a potential solution.

The Current Congress: Historically Unproductive

Newton’s first law of motion states that an object at rest stays at rest, and you need look no further than our current Congress for proof. As of December 2023, the current Congress bears the distinction of being the most unproductive in decades, only breaking records for most votes for House Speaker.

But the problem of congressional inaction has been with us for a while, and it’s only the recent set of crises that’s revealed how bad it is.

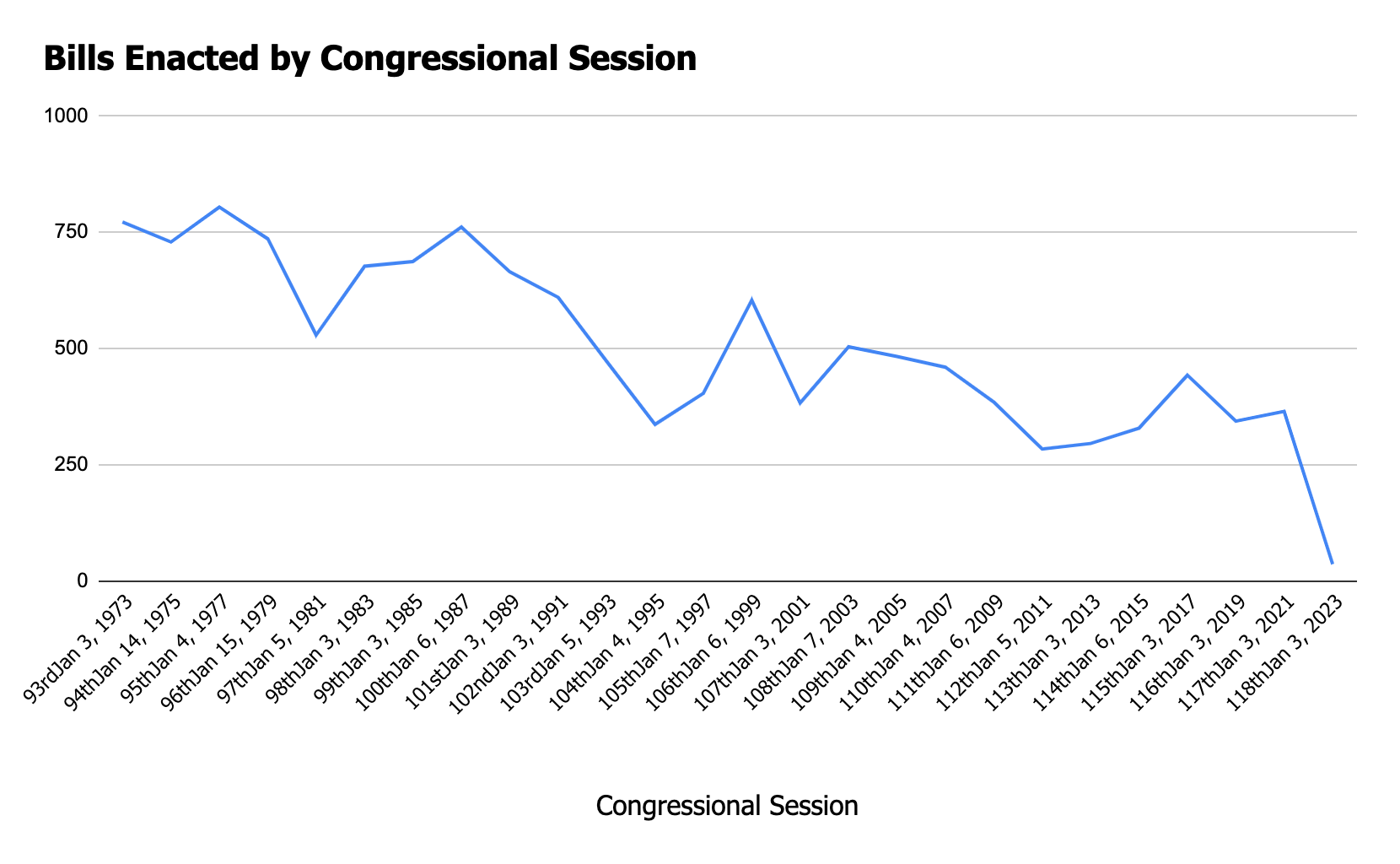

Over the past 20 years, the number of bills passed by Congress has been cut in half - falling from 772 in 1973 to 37 in 2023.

But passing more bills doesn’t necessarily mean a more effective government, as some would argue the government that governs best, governs least. So a fair question to ask would be how good is government at governing when they actually want to govern?

Not very.

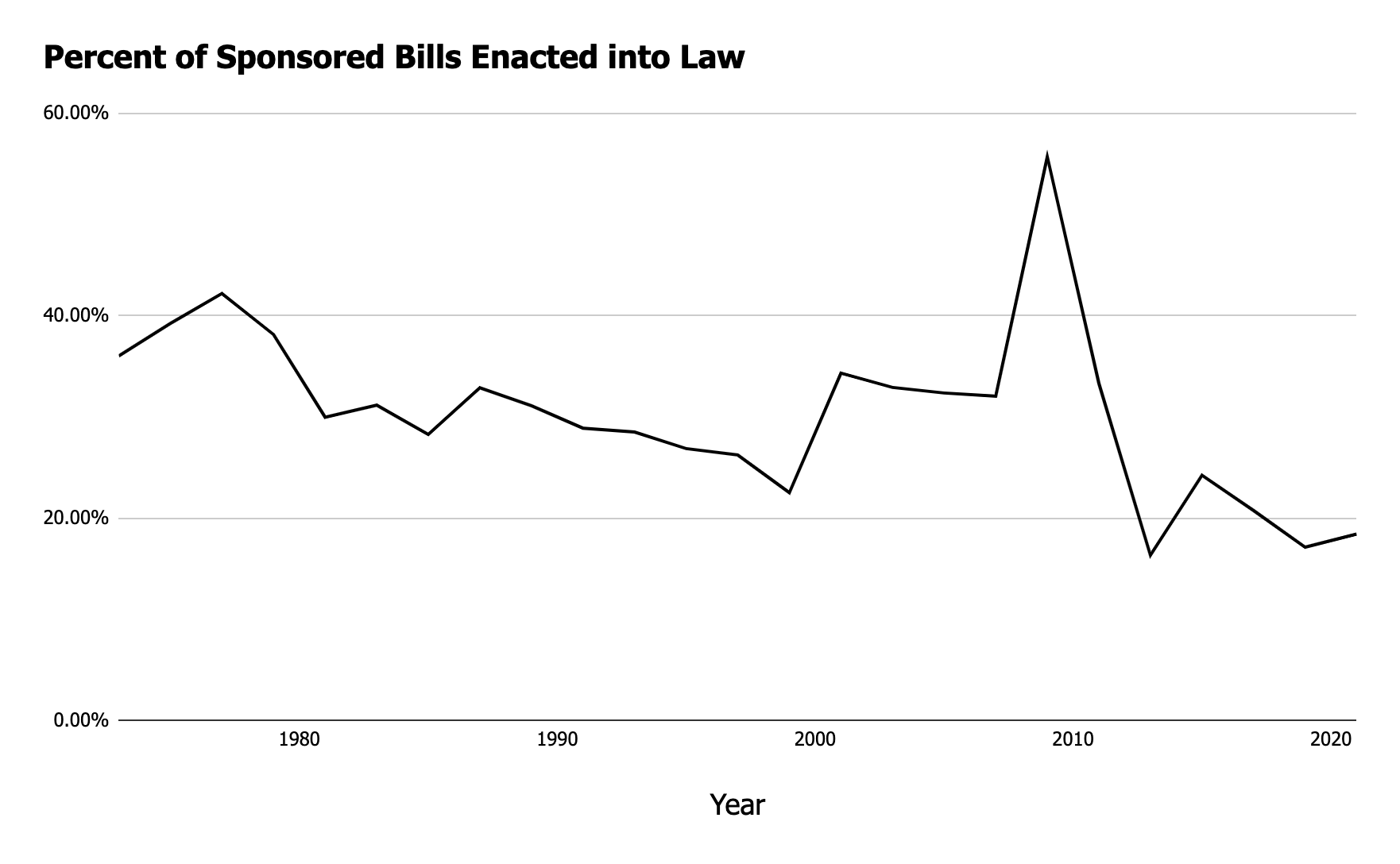

We can figure this out by looking at the percentage of sponsored bills that make it into law, as this measures the ability of members of Congress to build coalitions around specific issues and enact policy. Data from the Center for Effective Lawmaking shows the number of substantial bills - these are bills that affect policy, as opposed to ceremonial bills like the one that declared September 19th “National Talk Like a Pirate Day” - has been cut in half over the past 50 years, from a little under 40% in 1973 to under 20% in 2021.

You’ll notice the trend temporarily reverses during the George W Bush years and the first two years of Obama’s first term, however, it’s worth noting one party held the White House and both Chambers of Congress during 8 of those 10 years, and we had two politically galvanizing moments - 9/11 and the 2008 financial crisis.

What this tells us is that congressional productivity is more an issue of Congress being unable to engage in the type of negotiations and compromise necessary to get things done than it is Congress collectively deciding they’ve got nothing to do.

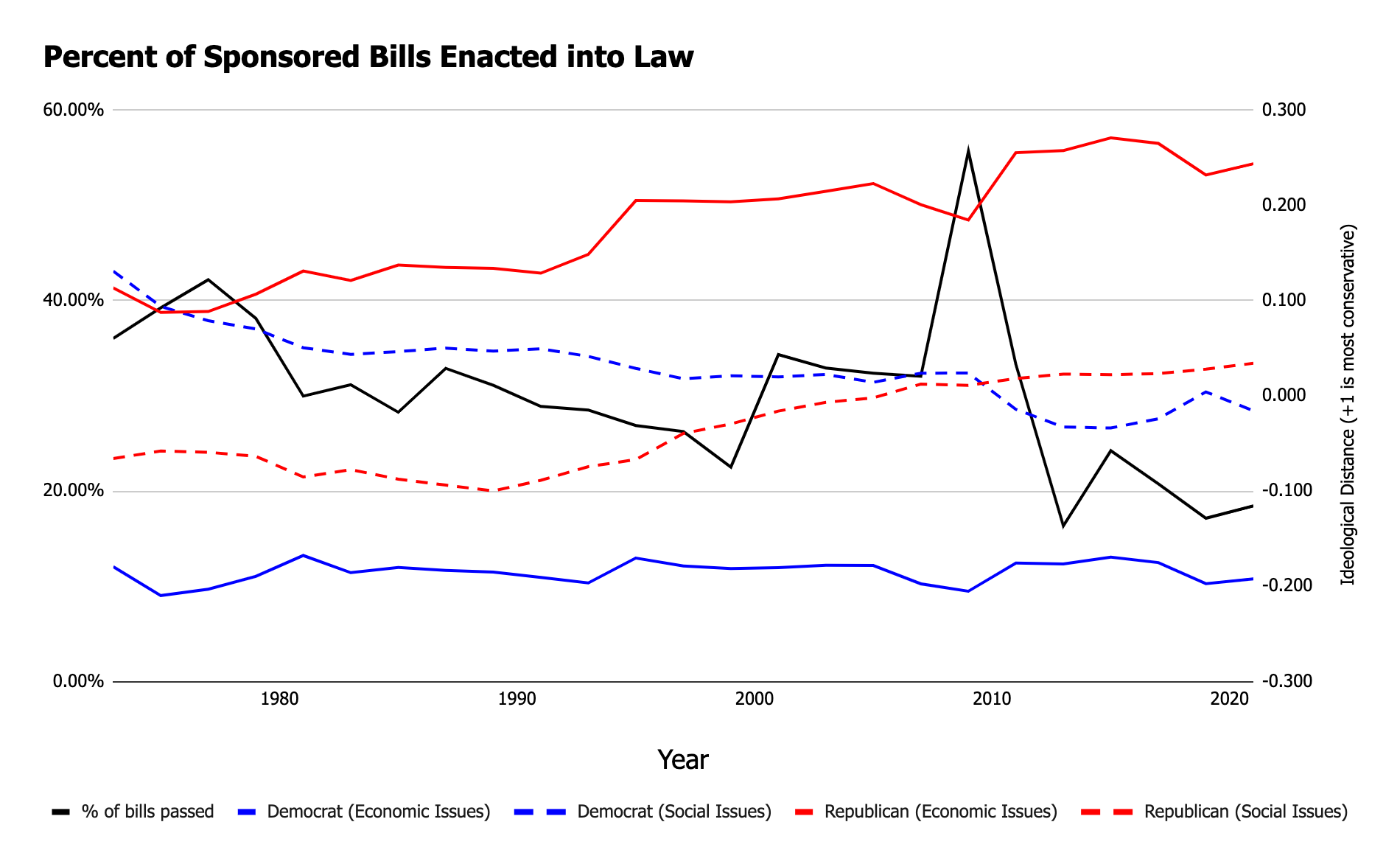

To drive the point home, here’s that same chart with the ideological distance between parties factored in (to calculate this, I used DW-Nominate data from Voteview, which you can read about here).

This is an eye chart, so I’m going to explain.

The solid red and blue lines represent how conservative or liberal the average Republican and Democrat voted on economic issues. These would be issues such as taxation and social spending.

The dotted line represents their voting patterns on social issues, which vary over time but have generally focused on issues such as civil rights, abortion, and gun control over the past 50 years.

What we see is that, as the ideological divide on economic issues increases over time, the ability of Congress to get stuff done decreases. We also see, oddly enough, that the distance on social issues is negligible, with Republicans being more liberal on social issues than their Democratic counterparts in the early 1970s.

(I’ve thrown enough at you with this chart, so we’ll save that topic for another day).

So, we know that political polarization is the main cause behind congressional gridlock, which would explain why Congress is unable to reach agreements on more polarized issues, but it doesn’t explain why they seem unable to enact legislation on popular measures, such as fixing the problem at the border.

For that, we need to look at another historical trend.

Safe Seats, Stagnant Congress

If we go back 20 years, there were 122 House seats deemed competitive by the Cook Political Report - meaning neither party had a margin of over 5% in these districts.

To put that another way, that means about a third of Congress could lose their job to someone from the opposite party if they didn’t keep the majority of voters happy.

By 2021, that number was down to 78 - about 18% of all seats.

So, where representatives in competitive districts have to worry about voters in the general election, the 80+% of Congress that serves in safe districts has to worry more about a primary threat from within their own party.

A study by Yale looked at the effect safe seats have on legislators and - go figure - the more a district was firmly in the hands of one party, the more partisan that district’s representative was.

Why?

Because if you’re a Democrat competing against another Democrat in a district dominated by Democrats in an election where only Democrats participate, you don’t win by trying to appeal to the middle - you win by campaigning further to the left than your opponent. The same holds true for Republican-dominated districts.

This also means legislators are beholden to a very small group of voters, as primaries tend to have lower turnout, assuming the incumbent faces a challenger at all.

A study by nonpartisan reform group Unite America found that, in 2022, about 8% of voters were responsible for electing 83% of US Representatives.

So, to put that another way, the chamber of Congress that’s supposed to be most representative of America is most representative of the most partisan 8% of Americans.

And that is why we can’t have nice things, folks.

So, while it’s fun to complain and all, how do we fix it?

Alaska - Recentering Elections

If House members are afraid to cross the aisle to solve problems out of fear of angering their base and invoking a primary challenge, then we need to change our system of elections to refocus candidates on the median voter.

In 2020, Alaska implemented a top-four primary system where all candidates competed for all voters in an open primary, and the top four vote-getters made it on the ballot in the general election.

This meant that candidates looking to get to the general election had to appeal to the same voters they’d be competing for in November, not just a partisan slice.

For the general election, they implemented ranked-choice voting - a system where voters rank their candidates in order of preference instead of just choosing one.

This meant candidates had to campaign for all voters, as being the first choice of your party’s base isn’t enough to get you over the 50% threshold to win office. Campaigning for the second and third-choice votes of independents and even members of the opposite party is a better strategy in this system than simply trying to tear your opponent down.

In the 2022 midterms, Democrat Mary Peltola beat out a challenge by a more partisan Republican, Sarah Palin, by winning 40% of the second-choice votes for Republican Nick Begich.

Pelota’s record so far includes recommending the formation of a governing majority in the House with more moderate Republicans to break the impasse over the election of House Speaker and bucking her own party in support of second amendment rights.

2022 also saw incumbent Republican Senator, Lisa Murkowski, reelected - the only Republican senator up for reelection in 2022 who voted to impeach Donald Trump after the January 6th attacks and one of four Republicans who voted to impeach to survive a Trump-backed primary challenge.

The other three come from districts with open primaries.

One other item of note - Murkowski and Peltola endorsed each other in the midterms.

If Alaska’s system can get party members to cross that divide, legislating shouldn’t be all that hard.