It’s been a month since Election Day, and we still don’t know who won the 2020 election! While it’s looking more and more clear every day that Joe Biden will be inaugurated in January, Donald Trump has yet to concede. At least the president has confirmed that he will step aside if the Electoral College votes for Joe Biden. Looks like we dodged WWIII and Civil War II this year:

Adding to the confusion, is the fact that a 73,700 vote swing Trump’s way in AZ, PA, and GA would have changed the Electoral College map in Trump’s favor (according to Marc Thiesson in the Washington Post). A shocking percentage of Trump supporters are certain the election was stolen.

Meanwhile Joe Biden’s supporters are heated that their candidate could have lost the Electoral College like Hillary Clinton did in 2016-- with a marked lead in popular votes.

This is an election that seems to have left no one happy.

It says a lot though about hyper partisan polarization-- and perhaps the need for voting reform and better standards for election security-- that millions of Americans talk like they’re certain who won, but they’re divided in half over just which one that happens to be!

Partisanship boiling over on your phone screen in real time is really something to behold.

Anyone else feel like Bill Murray’s character in Groundhog’s Day?

“Just put that little hand in mine, there’ll be no hill or mountain we can’t climb!”

And just like Phil, partisan voters are feeling more and more alienated with each passing day. They’ve already progressed from jaded:

“This is one time where television really fails to capture the true excitement of a large squirrel predicting the weather.”

To icily alienated from all the “idiots” and “hypocrites” who don’t see things the way we do:

“This is pitiful. A thousand people freezing their butts off waiting to worship a rat. What a hype. Groundhog Day used to mean something in this town. They used to pull the hog out, and they used to eat it. You're hypocrites, all of you!”

To desperately frustrated:

“There is no way that this winter is ever going to end as long as this groundhog keeps seeing his shadow. I don't see any other way out. He's got to be stopped. And I have to stop him.”

Naturally, supporters of Donald Trump, the apparent loser in this presidential election, are livid at a litany of irregularities and grievances related to the election.

But even Democrats don’t feel like they have much to celebrate, and they kind of don’t. They got a presidential candidate past the finish line who they weren’t really happy with anyway.

Joe Biden bears a striking resemblance to Trump in many non-trivial ways. They had to hold their nose to pull the lever for him. At least he wasn’t Trump.

Moreover, Democrats only picked up one seat in the Senate, not enough to humble Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and put Chuck Schumer (D-NY) back on top.

And they shockingly lost seven U.S. House seats, while Republicans picked up eight, narrowing the Party of Jefferson’s already thin majority in the lower house of Congress.

Source: New York Times

Democrats Push for Abolishing The Electoral College After Close Scrape with Donald Trump

So even after winning the presidential election (should Donald Trump fail in his campaign’s quixotic effort to successfully litigate alleged fraud and win these suits in multiple jurisdictions), Democrats are pushing for reform. They’re still not happy about Trump winning the Electoral College in 2016, despite losing the popular vote. And they’re even miffed that he easily could have won the EC again in 2020 if not-very-many votes had been different in three or four states.

To advocates of abolishing the Electoral College, it seems unfair, a gross disenfranchisement of voters, that Joe Biden could lead by nearly 6 million votes nationwide, yet still somehow lose.

It feels as if the will of the voters isn’t represented in that outcome.

And it certainly does appear that way. At least at first glance. Why did the Framers of the Constitution set it up so that this could happen?

To find out, we have to take a trip back in time.

"A Republic, If You Can Keep It?"

There’s an old (unverified, but enduring) story about the Constitutional Convention of 1787.

As Ben Franklin exited the convention, a passerby asked him what kind of government the American colonies would have. It was still quite possible at that moment in history, that America would have its own monarchy. That’s the only kind of government Americans had lived under.

One surviving letter from a Continental Army colonel even suggests some in the army were hoping George Washington would be America’s first king. They were worried Congress wouldn’t be willing to appropriate the necessary funds from the people to fairly compensate the soldiers their back pay and pension for the war. Congress being unwilling to spend money--

Now that’s something we can all laugh at this side of the Constitutional Convention!

Ben Franklin’s apocryphal reply to the passerby:

A republic, if you can keep it.

That has been the secret to America’s stability and success as the world’s oldest surviving democracy-- that it’s not only a democracy, in which the citizens vote, but also a federated republic. The Framers designed the Constitution so that the sometimes wild swings of popular sentiment are tempered by a system of checks and balances. In addition, the power of the federal government is balanced by the powers of the several sovereign states. And the powers of the several sovereign states are balanced against each other by the federal government.

The United States gets direct feedback from all eligible voters who choose to vote every two years. But it also mellows out that constant feedback, and acts as a pressure valve to blow off some steam by holding presidential elections every four years, and mediating them through the states.

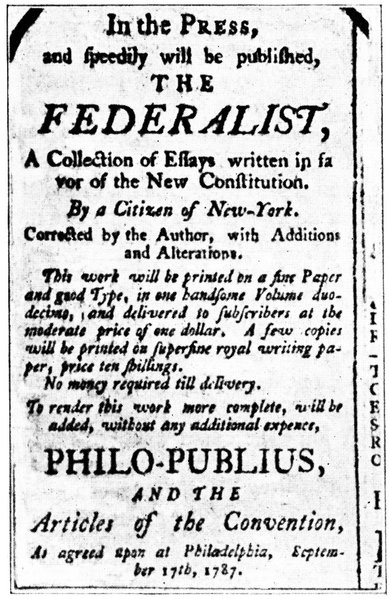

"In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions. This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights."

-ALEXANDER HAMILTON OR JAMES MADISON, FEDERALIST NO. 51

Of course, we also stagger senatorial elections every two years, with a third of the upper house’s seats up for election each time. Our constitutional republic is not a unitary government, but a federation of states. That’s been crucial to its ability to remain one, single, stable nation while growing much faster than most or all of the world in people, territory, wealth, and global influence over the last two-and-a-half centuries. The Electoral College system recognizes and supports the sovereignty of the fifty states by vesting them with the power of participation in the election of the president, along with that of voters, and by apportioning two extra electors to each state on top of the number of its congressional delegation determined by the census.

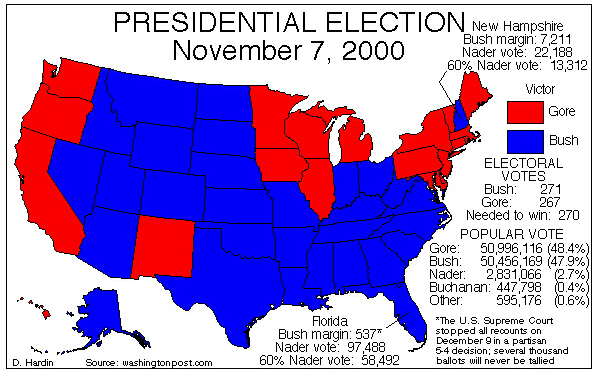

In the aftermath of Joe Biden’s close brush with another Electoral College “misfire,” as it’s called by critics of the system, like the one in 2016 that put Donald Trump in the Oval Office, and the one in 2000, which favored George W. Bush, many mainstream news outlets with a center-left audience called for an end to the electoral college. On election night, “Electoral College” was a worldwide trending term on Twitter, with a raucous chorus calling for a popular vote reform.

NPR, Washington Post: End The Electoral College

On Nov 16, National Public Radio aired a segment entitled, “The Electoral College: Why We Still Use It And How To End It.” In the panel discussion, Democratic Elector Nina Ahmad of PA, and authors Ned Foley and David Litt joined the station’s 1A podcast to thrash it out. NPR’s teaser reads in part:

“Democrats have won the most votes in seven of the last eight presidential elections. So why did a Democrat only become President in five of them? You can blame (or thank) the Electoral College. The Electoral College will meet next month to vote. President-elect Joe Biden is expected to win.

But why do we even have a system where the victor could be someone who didn't win a majority of votes?”

The day before, the editorial board of the Washington Post ran an opinion piece headlined: “Abolish the electoral college.” In it, the Post staff said:

"It is alarming that a candidate came so close to winning while polling more than 5 million fewer votes... The electoral college, whatever virtues it may have had for the Founding Fathers, is no longer tenable for American democracy."

But not much further down, after summarizing the arguments against reforming the Electoral College, and acknowledging how unlikely such a reform is to happen, the Washington Post editors reveal what appears to be the real animus behind their call for abolishing the Electoral College:

To them it is alarming that Donald Trump, not just any candidate, came so close to winning the Electoral College while losing the popular vote:

“Mr. Trump became president in 2016 despite earning 3 million fewer votes than Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton.

Now, he has come close to winning reelection despite losing the popular vote by a far greater margin…

We believe that Mr. Trump’s election was a sad event for the nation; his reelection would have been a calamity.”

They insist this is not the case at all, and that their call to end the Electoral College is not a short-sighted, partisan tactic in the guise of a simple, common sense-- but in fact very complicated and truly radical-- rewriting in the foundations of our form of government.

They assure the reader they would be saying this regardless of which way the EC misfire cuts:

“But we would be making this argument no matter which party seemed likely to benefit. If Democratic nominee John F. Kerry hadn’t lost Ohio by just 120,000 votes in 2004, he would have won an electoral college victory despite trailing President George W. Bush by 3 million votes in the national count.

That would have been a problem, too.”

But there was no similar opinion piece on the Electoral College from the Washington Post editors in 2004. A simple Google search for “electoral college site:washingtonpost.com” Aug 1, 2004 - Mar 1, 2005 returns no such result. The closest thing to it is a study guide the Post made for students, “Should the electoral college count?” with no position taken, of course.

Fred Hiatt, the editor of the Post’s editorial page has been in his position since 2000, and on the board since 1996. Can we take this plea of partisan objectivity seriously?

A Partisan Strategy, Disguised as a Modest Reform, In Search of A Crisis

According to the Congressional Research Service, there have been only four so-called Electoral College “misfires” in US history. The only two to occur in the last century delivered America its most recent two Republican presidents. The Post editorial board doth protest too much methinks.

What this looks very much like to me, is a thinly concealed attempt by Democrats to make their party a permanent majority party in the White House in the US. This partisan motivation cannot lead anywhere good, because it doesn’t consider the nature and consequences of such a drastic reform in good faith for reasons of improving US statecraft.

One of the unintended consequences would be to give cities, and the interests of the more populous section of American voters who live in major metros undue influence over the levers of executive power, and the de facto leaders of the two major parties-- their presidents.

The Washington Post editors ask:

“But why should Iowa’s biofuel lobby get more of a hearing than, say, California’s artichoke lobby? Small states already have disproportionate clout in our government because of the Senate, in which Wyoming’s fewer than 600,000 residents have as much representation as California’s 39.5 million.”

While there are fewer people living in more sparsely populated regions, their contributions to society, and proper attention and care to their interests is absolutely vital. They’re the ones who feed us and many other countries in the world.

While California has the largest agricultural industry of the 50 states by annual agricultural cash receipts, its per capital food output is a blip next to that of Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Wisconsin, South Dakota, Arkansas, and Idaho. See recent figures published by Beef Market Central for reference. Do their votes "weigh more" in the Electoral College?

Should the votes of people packed together in cities, who are of like mind because they live in proximity and share interests weigh more? Are those votes really representing different interests, or a multiplicity of people densely packed into regions and industries with the same interests?

In Federalist No. 39, James Madison fears the interests of a passionate majority could overrun the less numerous, but equally vital interests of some minority in a system of direct democracy, unmediated by the Founders’ checks and balances:

“A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party or an obnoxious individual.”

Earlier, in Federalist No. 10, Madison noted:

“Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty, that our governments are too unstable, that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties, and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority.”

He and the other Framers of the US Constitution would be decidedly opposed in principle to the conclusion of the Washington Posts’ editors in “Abolish the electoral college,” which reads:

“Americans are not going to be satisfied with leaders who have been rejected by a majority of voters, and they’re right not to be. It’s time to let the majority rule.”

This is no self-interested elitism for the protection of those with the most money and power, as critics of the Electoral College might cast it. Keeping farmers in Iowa safe from being overrun by wealthier and more numerous stock brokers in New York City and Big Tech executives and major equity stakeholders in Silicon Valley is very much looking out for the little guy.

What is to stop Midwestern farmers, whom we depend upon for enough food, from becoming a subsidiary of Amazon Inc without some pressure valves for the undue influence of a well-funded majority built into our constitutional system of government?

It is self-evident that a nation should always have too much food, rather than not enough. Far from being antiquated, these concerns the Founders had for protecting less populous interests from the tyranny of the majority are more pressing today than when the Constitution was written.

Back then the population density ratio of urban areas to non-urban areas in the US was not as extreme as it is today. In 1800, the nation’s largest city, New York City, had 60,514 inhabitants, against the nation’s 5.3 million people, for a .011% share of the total population.

Today, with a population of some 8.33 million people, New York City makes up a .025% share of the total US population of some 332.6 million US residents. That’s more than twice as numerous, and but with far more than twice-and-a-half again the financial clout of the NYC of the year 1800.

The reasons the Founders had for the Electoral College, which has worked out well enough for the United States, we can maybe all agree, are far more pronounced today than ever.

Screen shots from:

"Groundhog Day" 1993 (Columbia Pictures) - For cultural commentary and educational purposes.