Gilbert Polanco is described as a man who was “proud of his job” and represented "the best of CDCR.” After working at San Quentin State Prison for three decades, Polanco became infected with COVID-19 and died Aug. 9 — two weeks before his 30th wedding anniversary. He was 55.

Polanco is one of nine California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) employees to have died from COVID-19, a disease that, according to staff who spoke anonymously to IVN San Diego, described as a wildfire spreading through the prison system that’s already claimed the lives of 54 inmates. These employees say there’s limited control of the wildfire-like spread due to testing delays and inadequate tracking procedures.

“It’s a complete failure on the part of the department to take seriously testing, contact tracing... to take seriously the importance of protecting its staff and how that it relates to protecting inmates,” said one CDCR employee. “There’s clear evidence of causation when you have a positive staff member and their patients — in this case, inmates — get positive results. The pandemic is like a California wildfire in the prisons. It just takes one spark. Employees are that spark.”

As of Aug. 14, the CDCR reported 1,040 active cases of COVID-19 among inmates at its more than 30 institutions across the state. More than 7,700 inmates have recovered from the disease, according to the department.

Among CDCR staff, which includes employees at prisons and those at headquarters in Sacramento, there are more than 1,000 active cases and a total of more than 2,200 cases as of Aug. 14.

CDCR is home to more than 100,000 inmates with 15.9 percent who are considered “high-risk,” according to internal sources. Inmates who are considered "high-risk" have at least one risk factor, including diseases such as ischemic heart disease, liver disease or HIV. Being 65 or older is also classified as “high-risk.”

Testing for COVID-19

Dana Simas, CDCR press secretary, said the department began mandatory COVID-19 testing of inmates on March 10, followed by mandatory staff testing on May 15. Staff testing began after CDCR, along with the California Department of Public Health and county public health officials, developed a testing plan, she said.

“CDCR and CCHCS (California Correctional Health Care Services) have been strongly committed to responding to this public health emergency and to protecting both staff and the incarcerated population,” Simas said. “We have worked tirelessly to implement measures in the face of a brand new virus, inherent constraints that exist with a critical 24/7 operation that involves hundreds of thousands of individuals and their loved ones, and outside constraints on availability of testing and resources that have also impacted the community at-large.”

However, several CDCR sources said although mandated staff testing began at some prisons following outbreaks, statewide mandated testing did not begin until weeks later.

An internal memo sent to CDCR employees on July 1 and obtained by IVN San Diego read “Beginning today, CDCR has begun the process of testing all staff in adult institutions for COVID-19. Prior to now, staff have been tested in institutions experiencing outbreaks. CDCR has committed to the federal court that baseline staff testing for all adult institutions will be completed by July 16, 2020.”

The CDCR memo came after U.S. District Judge Jon Tigar released a federal order stating, “that baseline testing of all staff at all institutions is scheduled to be completed by July 16 at the latest.” The order was a part of a series of lawsuits in the Marciano Plata vs. Gavin Newson case in an effort to improve medical care at CDCR.

Sophie Hart, an attorney with the Prison Law Office, the firm litigating the case, said the most recent data from CDCR indicates “hundreds of staff members still haven't been tested.”

“The (CDCR) plan also doesn’t call for testing staff with symptoms of COVID – instead, it says CDCR will send staff home and direct them to seek a medical evaluation,” said Hart. “There’s nothing in the plan about following up with that staff person to make sure they saw a doctor and received a test. There’s also nothing in the plan requiring that an staff person to report their test results to CDCR, so it’s unclear how CDCR will know if the staff member tests positive.”

Simas, the CDCR spokesperson, defended the department, stating it has conducted more than 76,000 tests, which is “almost three times the state and national testing rate.”

The department has “worked tirelessly to implement measures in the face of a brand new virus, inherent constraints that exist with a critical 24/7 operation that involves hundreds of thousands of individuals and their loved ones, and outside constraints on availability of testing and resources that have also impacted the community at-large,” Simas said.

Simas also noted efforts in “suspending intake from county jails, reducing the density in dorms and other housing units, suspending in-person visiting and volunteering and expediting releases of eligible incarcerated persons.”

CDCR has also revised intake and transportation procedures following a transfer of more than 100 high-risk inmates from the California Institution for Men in Chino to San Quentin State Prison and provides face masks and hand sanitizer to inmates and staff.

Despite these efforts, Hart noted that employees are still moving from yard to yard, which could further spread the disease. She said CDCR has not yet grouped staff or assigned them to work in specific yards or buildings.

“Officers are typically assigned to one spot as their primary work location, but they are free to — and often do — pick up shifts in other areas of the prison,” said Hart.

Testing Turnaround Times

Last month, MiraDx, a molecular genetics company based in Los Angeles, was awarded a $150 million contract to provide coronavirus testing services to CDCR for the next year. The company says it has the capacity to analyze over 9,000 tests per day with no backlog and provide results within 48 hours after it receives samples. Expedited processing is available within 24 hours.

However, CDCR employees told IVN San Diego results sometimes take up to 10 days.

Once test results are available, prison employees receive an automated email from MiraDX detailing the date samples were taken and the date test results were sent to employees. Several of these emails obtained by IVN San Diego indicate they were sent more than 48 hours after laboratory work was completed.

“If it takes 10 days to get my results, it begs the question: I wasn’t positive 10 days ago, but what about now?” one CDCR employee said. “We’re just late doing anything. Bureaucracy is slow.”

Another prison worker echoed complaints about delays in being notified and told IVN San Diego that frequently they are forced to follow-up themselves if they want their results.

“They won’t even tell you if your results are in,” the CDCR employee said. “The results run so late so there are many, many missed days and opportunities. If I’m a housing unit officer, the movement is restrictive, which is good, but if the officer doesn’t know his results until a week later and he’s interacting with vulnerable inmates — that’s a problem.”

However, a MiraDx spokesperson denied claims that results take 10 days to be returned.

“MiraDx is one of several labs doing testing for CDCR employees and our typical turnaround time is 48-72 hours,” the spokesperson said. “Just a week ago, we did surge testing at one prison with turnaround time under 24 hours, and currently have turnaround times of approximately two business days. We’ve never had a backlog that resulted in a 10-day turnaround time. We are always looking to improve our processes but generally, we are pleased with our overall processing rates since program inception. We also are working closely with our CDCR partners to continue improving the overall testing process.”

Separately, CDCR also signed a $42 million contract with Mobile-Med Work Health Solutions Inc., of San Jose, to provide testing services through June 30, 2021. Emeryville Occupational Medical Center, the department’s existing vendor for tuberculosis tests and personal protective equipment, also provided COVID-19 testing.

Both the MiraDx and Mobile-Med contracts were awarded under an emergency declaration that did not require bidding. The contract notes that the Federal Emergency Management Agency may provide some sort of reimbursement for the amount spent on testing.

Tracing COVID-19

Prison employees told IVN San Diego they are frustrated because contact tracing has been “rocky.” Some employees said they had not been informed after a co-worker tested positive.

“Nobody knew I was in quarantine for days until I told them,” one CDCR employee told IVN San Diego. “The contact tracer is really no contact tracer.”

When asked about contact tracing, Simas referred IVN San Diego to an article appearing in the department’s internal employee newsletter “Inside CDR.”

That article reported the CDCR public health nurse is “well versed on the importance and effectiveness of immediate isolation and quarantine, physical distancing, proper hygiene, and hand-washing, some of which was largely unknown to the public until the COVID-19 pandemic hit our community.”

“Immediately identifying those who have the virus, isolating them from others, and quarantining those who have been in contact with the positive patient, are all critical steps to mitigating the spread of any communicable disease,” continued the article. “In the event an incarcerated person develops symptoms, nursing staff at the institution immediately isolate the patient and conduct a COVID-19 test. If the result is positive, or is suspected of being positive, CCHCS nursing and public health staff begin the process of contact tracing within the institution.”

Still, employees said the effectiveness of contact tracing was a concern.

“They aren’t transparent if employees test positive so it makes you wonder, ‘Was it the nurse I worked with yesterday and that’s why he isn’t here today?’” an employee said. “We probably have a lot of staff that wouldn’t be able to come into work if they properly traced (the disease).”

CDCR administration does provide a list of guidelines for employees if they test positive for COVID-19, including the requirement to self-isolate at home. However, a July 9 email to employees said “Staff who are pending a COVID test result and are asymptomatic can continue to work while wearing face coverings and utilizing appropriate PPE. All staff should be screened for fever, respiratory symptoms or other COVID-related symptoms each time they enter any institution.”

Oversight and Complexity

Several key players have provided feedback to CDCR on how to mitigate the disease within prison walls, including the California Correctional Peace Officers Association and SEIU Local 1000, which filed a grievance against CDCR earlier this month.

Glen Stailey, the president of CCPOA, issued a statement to IVN San Diego, saying “the nature of a correctional facility makes adherence to public health guidelines more difficult than it is outside the wire.”

“Our members deserve safe working conditions, and they are rightfully concerned that by coming in to work they may be exposing their families to the virus,” Stailey said. “Now that it’s clear the virus will be with us for some time, we are doing our best to advocate for California’s correctional officers so that they have both the equipment and safety procedures that they need to do their job.”

The Office of the Inspector General, which oversees CDCR, was also asked to review the department's response to COVID-19. The agency released its first review on Monday, detailing inconsistencies with screening for the disease among essential visitors. The report noted each prison had its own way of screening visitors, including some prisons that screened visitors before they exited their cars, while other prisons screened visitors after they left their cars. In some instances, "thermometers, which were used to check the temperatures of each person during screening, did not always work properly," the report said.

Despite recommendations and oversight, several challenges should be considered when examining COVID-19 in prisons, experts say.

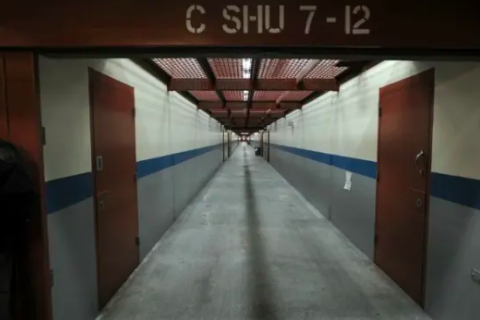

Steffanie Strathdee, associate dean of global health sciences at UCSD's Department of Medicine who focuses on vulnerable populations, described prisons and jails as a “perfect storm for transmission” of the novel coronavirus.

“In the U.S., (prisons and jails) are very overcrowded, and when people are in close quarters, the droplets and aerosols that transmit the coronavirus are more likely to infect people,” Strathdee said. “In addition, the health care infrastructure in prisons and jails is fragmented and not set up to deal with an outbreak, so they are less able to cope with a large number of prisoners requiring testing or urgent care.”

Given the challenges, Strathdee said “unless test results can be turned around within 24-48 hours, they are pretty meaningless. By then, prisoners who are infected could have transmitted the virus to many others. In my view, prisons and jails should be de-populated in the midst of a pandemic like this. Few leaders have been willing to take on this bold measure, and several communities have paid the price.”

But, State Sen. John Moorlach (R-Costa Mesa) — who sits on the Senate Committee on Public Safety, which held an oversight hearing regarding COVID-19 in state prisons on July 1 — said “there are no easy answers here.”

Moorlach addressed employees’ concerns in an interview with IVN San Diego. He also criticized transfers of inmates that led to the outbreak such as that of San Quentin State Prison.

“There’s obviously some lack of thorough management decisions,” Moorlach said. “We need to look into the testing system, what the turnaround time is, who is being appropriately sensitive to everybody affected. There needs to be better collaboration.”

Among the people affected by the decisions at CDCR are the family members of Polanco, the San Quentin State Prison correctional officer who died earlier this month. His daughter and wife also tested positive for COVID-19.

“We all go home to families,” a CDCR employee said. “If you don't care about inmates, maybe you don't care about how your tax dollars are spent, but surely the public can empathize with a person who unwittingly exposes their family and perhaps the larger community.”

This story was updated at 11:30 a.m. Monday to include information from the Office of the Inspector General's first review of COVID-19 within California's prison system.