Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in The New York Times and has been republished on IVN with permission from the author.

In his farewell address to the nation, President Dwight Eisenhower issued a warning: “In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Eisenhower, who in his military career had commanded Allied forces in Europe against the Nazis, delivered those remarks in January 1961, at the height of the Cold War, which had led to a drastic militarization of American society.

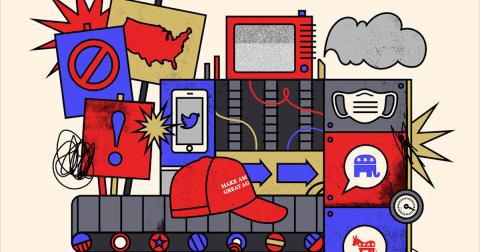

In the nearly 60 years since Eisenhower’s address, the term “industrial complex” has been used often to describe the self-justifying and self-perpetuating nature of various industries — medicine, entertainment and education, to name a few. But it is the political incarnation that we are most dangerously mired in now. Just as the military-industrial complex threatened to undermine democracy in Eisenhower’s time, the political-industrial complex threatens to undermine democracy in ours.

A recent analysis in the Harvard Business Review by Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter describes this systemic threat succinctly:

Far from being “broken,” our political system is doing precisely what it’s designed to do. It wasn’t built to deliver results in the public interest or to foster policy innovation, nor does it demand accountability for failure to do so. Instead, most of the rules that shape day-to-day behavior and outcomes have been perversely optimized — or even expressly created — by and for the benefit of the entrenched duopoly at the center of our political system: the Democrats and the Republicans (and the actors surrounding them), what collectively we call the political-industrial complex.

This political-industrial complex includes not only legions of campaign staffers, pollsters, consultants and other party functionaries, but also media (both traditional and nontraditional) that inspire division because division keeps people engaged, keeps eyeballs on screens, and so drives profit.

While average prime-time viewership across the top three cable news channels had fallen by roughly a third from 2008 to 2014, the advent of Donald Trump’s candidacy and election caused viewership to soar, with CNN posting nearly $1 billion in profits in 2016. This trend has persisted. As The Times’s Michael M. Grynbaum reported in August: “In June and July, Fox News was the highest-rated television channel in the prime-time hours of 8 to 11 p.m. Not just on cable. Not just among news networks. All of television.”

The effects of this complex extend far outside politics. Today, nearly every facet of life falls somewhere along the left-right political spectrum. Every question we ask ourselves is shot through the lens of politics. I am, for instance, a divorced father with a third grader and a fourth grader, and I desperately want them in school, with their friends. When speaking to other parents, does my fervent desire to see them in school, even as we grapple with the coronavirus, make me a Trump supporter? A Republican?

I am also a veteran. When I tell my military buddies that prisoners of war should never be slandered, do they assume that I’m also a fan of the Green New Deal? A Democrat? The politicization of American life is swiftly becoming total, with virtually no opinion or thought existing outside the realm of partisan sorting.

In 1939, when America was emerging from the throes of the Great Depression, our military ranked 19th largest in the world, standing behind Portugal. World War II, and the Cold War that followed, epitomized what theorists call “total war,” in which every facet of a society is mobilized. This was a departure from centuries past where nations typically waged “limited war,” relying on professional armies instead of the widespread enlistment of its citizenry and means of national production. One consequence of total war is that even nonmilitary parts of society become military targets: manufacturing, agriculture, energy, even civilian populations.

By the time Eisenhower delivered his address, total war had reached its zenith, as the development of civilization-ending nuclear weapons had made the human race’s continued existence contingent on a precarious doctrine of “mutually assured destruction” between the United States and the Soviet Union.

One way to measure our current state of “total politics” is to look at the economics of our presidential campaigns. In the 1980 presidential election, spending by Republicans and Democrats combined totaled $60 million dollars ($190 million today when adjusted for inflation). In this year’s presidential election, advertising alone is projected to reach $7 billion, in itself a 37-times increase in spending. According to the Federal Election Commission, presidential candidates spent $2.3 billion from Jan. 1, 2019, through March 31, 2020.

The military-industrial complex fed off the U.S.-Soviet Cold War conflict in much the same way the political-industrial complex feeds off the left-right conflict. If the military-industrial complex led us into a paradigm of perpetual wars with little hope of victory and no end in sight (Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq), then the political-industrial complex has led us into a paradigm of perpetual campaigns in which our political class needs divisive issues to fight over more than it needs solutions to the issues themselves — crucial issues like gun control, immigration and health care.

What can we do?

Worthy initiatives like ranked-choice voting and gerrymandering reform may help; however, the first step is for each of us simply to become aware of the ways our passions are being inflamed and manipulated for profit and how the political-industrial complex feeds off our basest fears of one another. Our experiment in democracy has worked when it appeals to the best in us, as opposed to the worst.

Eisenhower knew this, and it was that instinct in each of us that he appealed to as he closed his farewell address: “Down the long lane of the history yet to be written America knows that this world of ours, ever growing smaller, must avoid becoming a community of dreadful fear and hate, and be, instead, a proud confederation of mutual trust and respect.”

And if we do become a community of dreadful fear and hate?

In the Cold War, failure meant mutually assured destruction through nuclear war. It was an outcome that, fortunately, never arrived, though it’s instructive that Eisenhower’s farewell address came a little less than two years before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the closest humanity has ever come to nuclear annihilation.

Today, we sit on a different sort of precipice as the American body politic hurtles toward the 2020 election. Both sides are laying groundwork to contest the result. Are we entering an era where we hold elections in a nation so hopelessly divided that neither side is willing to accept defeat? In a democracy, that is the truest form of mutually assured destruction.