Louisiana's fake nonpartisan primary system should be distinguished from successful nonpartisan systems in California and Washington state by two significant differences: (1) if a candidate receives more than 50 percent of the vote in a primary, they don't even hold a general election; and (2) Louisiana has some of the most gerrymandered districts in the country.

While technically the Louisiana system is 'nonpartisan,' parties have used the legislative process to mitigate its nonpartisan effect. Instead of opening up the system to more voters, as proven effective in Washington state and California, Louisiana's primaries have often reduced voter choice and pushed voter turnout to some of the lowest levels in the country.

In a non-obstructed blanket nonpartisan primary, all the candidates for an office run together in one election. The top two candidates then have a runoff in the general elections, unless one person wins a majority (over 50 percent of the vote). If that is the case, there is no general election and the winner is able to assume the office for which they ran.

Louisiana's 'nonpartisan' system has been used in statewide elections since 1975. It has also been used for federal congressional seats since this time for all, but a brief interlude of four years in the early 2000.Originally, Louisiana lawmakers decided to change their system when then-Governor Edwin Edwards ran in the early 1970s in two grueling rounds of the Democratic Primary in 1971 and then had to face a well-funded and well-rested Republican opponent, David Treed. Therefore, Edwards thought it might make general elections fairer to have a blanket primary since both candidates would have been through the same primary process.

Many political analysts also see blanket nonpartisan primaries as a way to moderate elections, by allowing independents to bring the conversation back to the middle and away from the party extremities that often emerge in partisan primaries.

In addition, blanket primaries are viewed as allowing for more choices, since independents or third party candidates can run in this system as opposed to being excluded from the first wave of elections, which often happens in many states like New York.

Despite these objectives, in Louisiana, this has rarely been the result because the parties have otherwise 'rigged' the rules in their favor.

A survey of election results in Louisiana, conducted in 2004, reveals that Louisiana's election laws may actually hinder both goals of moderation and expanding choice, whereas nonpartisan primaries in states like California have had a positive effect on moderation.

A large part of Lousiana's troubles could be that, in most cases, runoffs do not even occur, because the majority party's candidate in heavily gerrymandered districts receive more than 50 percent of the vote in the low-turnout primary, before 'regular' voters come out to the polls.

For example, in Louisiana’s congressional elections in 1998, 5 of the 7 U.S. House seats faced no opposition at all, with a sixth election failing to go past the first round.

This pattern occurred throughout the 1990s: three seats uncontested in 1996, no general elections at all in 1994, and 6 of 7 in 1992 also won by landslides, clearly reducing voter choice.

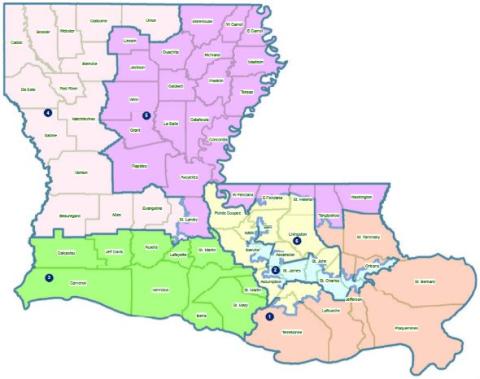

Political gerrymandering proved most poignant in the past few years when Louisiana’s congressional delegation shrunk from 7 representatives to 6. As a result, Republicans and Democrats fought over what these new districts would look like so they could protect their majorities.Louisiana came under great scrutiny in 2011 as the Republican-dominated legislature was widely seen as distorting partisan representation, breaking up natural communities, and under-representing racial minorities to ensure continued Republican success. The redistricting efforts largely ensured that races in Louisiana would even further produce noncompetitive races.

In 2012, 5 of the 6 Louisiana congressional elections were cut short after the primary.

The lack of viable choices for Louisiana voters had even further implications regarding voter turnout. Throughout the decade, for example, Louisiana often ranked among the lowest in voter turnout in the entire nation. This highlights the negative consequences that a primary "winner-takes-all" rule creates.

Around the country, political pundits use the Louisiana primary system as an example of how nonpartisan primaries don't solve the problem with partisanship. The problem with this comparison is that Louisiana has unique rules from other nonpartisan systems like California and Washington state, crafted carefully by the political parties to prevent nonpartisan participation. What this suggests is that parties can work together to draw districts and write laws that insulate themselves even from nonpartisan reforms.