“If a man, who had adopted a son and reared him, founded a household, and had children, wish to put this adopted son out, then this son shall not simply go his way. His adoptive father shall give him of his wealth one-third of a child's portion, and then he may go. He shall not give him of the field, garden, and house.” —Hammurabi’s Code, Item 191

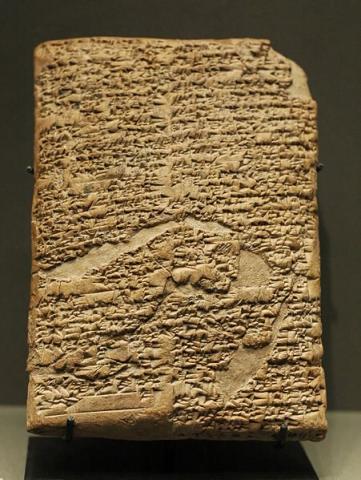

Judges and politicians in Ancient Babylon had a pretty easy job. The great King, Hammurabi, wrote down all 282 things that (he thought) judges could ever be called upon to decide. And then he told them what to do. Easy-peasy—judging was just a matter of applying a set of decision rules.

For all of its advantages, the Hammurabi model of lawmaking did not appeal much to the framers of the American Constitution. They understood all too well that this was just a way to extend a dictatorship in time and place, and they wanted to do something very different, which was to create an instrument that would allow people to govern themselves.

For the most part (but not always) this has worked out pretty well. By design, the Constitution creates a political structure that enables people from very different backgrounds to come together, debate the issues that are important to them, and forge the kinds of compromises that are essential for a large country—be it thirteen colonies or fifty states—to govern itself. This is hard work. It is supposed to be hard work. Kings and dictators are often successful because they relieve us of the need to do the hard work of governing ourselves.One of the greatest threats to self-government in a constitutional system like ours is the attempt to turn the Constitution into something like Hammurabi’s Code—a hard-and-fast set of rules that tell us what to do in every situation. The Framers did almost everything that they could to prevent this from happening.

The Constitution sets up a deliberative environment. It says very little about specific issues, and it often uses intentionally ambiguous phrases (i.e. “general welfare,” “necessary and proper,” “all needful rules and regulations”) that were specifically designed to be interpreted differently in different situations. Almost always, the specific wording of the Constitution reflects compromises that the largely Federalist framers made for the sake of ratification. The Constitution was steeped in compromises from the very beginning.

Nowhere is this more evident than it is in the wording of the Second Amendment, “a well-regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” The ink was not dry on the Bill of Rights before people began to look for absolutes in an Amendment that was specifically designed as a compromise between Federalists like George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, who did not trust the state militias that they had seen in the Revolutionary War, and anti-Federalists like Patrick Henry and John Hancock, who wanted to write an amendment forbidding the establishment of a standing army.

Somehow, however, the Second Amendment, which was born in compromise, has become a point upon which compromise is now impossible. We have this debate every time that something horrific happens involving guns. Some say that gun ownership is a collective right only granted to militias, while others insist that the Second Amendment forbids any regulations on gun ownership for any reason. Neither statement can stand even basic historical scrutiny about the state of militias and weapon ownership in the Founding Era.

More importantly, however, trying to turn the Second Amendment into a clear and absolute ruling on a problem that the Framers of the Constitution did not have is to misunderstand the purpose of things like the Constitution. Our Constitutional system works largely because of its minimalism. It is a very different document from the Code of Hammurabi or the law of Moses. These legal codes were designed to govern people; the Constitution was designed to give people a mechanism for governing themselves. That each generation do so is the clear intent of the document.