Part 2 of 3

“The idols of the tribe are inherent in human nature, and the very tribe or race of man. For man's sense is falsely asserted to be the standard of things. On the contrary, all the perceptions, both of the senses and the mind, bear reference to man, and not to the universe, and the human mind resembles those uneven mirrors, which impart their own properties to different objects, from which rays are emitted, and distort and disfigure them.”—Francis Bacon, Novum Organum

The only time I ever got in trouble in high school was the time I bet against our football team. It wasn’t much of a bet—just a dollar. And I lost. But, somehow, my journalism teacher/newspaper advisor found out about it told me that if she had known I was capable of such perfidy, she would never have picked me for the newspaper staff—and if she could, she would fail me for the semester. For about a month, I was a persona with very little grata.

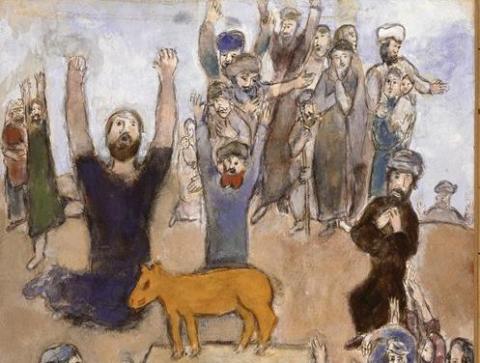

Actually, I got off pretty easy. Dante would have sent me to the ninth level of hell, and lots of other people throughout history would have killed me. Human beings evolved almost entirely in an environment dominated by tribes and clans where in-group loyalty was essential to survival. We learned to think in reference to in-groups and out-groups, and we learned to enforce tribal loyalty by shunning, exiling, or killing anyone who betrayed the interests of the tribe. Never take sides against the family, Fredo, or you end up at the bottom of the lake.

One of the key insights in Matthew Levendusky’s wonderful book The Partisan Sort is that modern political parties function as tribal, rather than ideological, groupings. Once somebody has self-identified with a political party, or joined the tribe, they will almost always resolve conflicts between their party and their personal beliefs by changing their beliefs to match those of their party. Only very rarely do people change their party affiliations to match their personal belief systems (3).

If Levendusky’s research here is correct then much of what we believe intuitively about political parties is wrong. In an electorate that has been “sorted”—i.e. one in which a large number of people have aligned with political parties that they perceive as representative of their beliefs—parties elites are not driven to adopt extreme positions by their base. Quite the reverse: the majority of the people who identify with a party will ultimately take their ideological cues from party elites. Parties move people much more than people move parties.

Here is another way to say it: most people want to be the kind of people that they think that they are--and we look to elite "role models" to tell us what we are supposed to be. This is true of those who identify as “Republicans” or “Democrats.” But it is also true of any other political tribe: “conservative,’ “liberal,” “moderate,” “independent,” “libertarian,” or “mugwump.” Once we determine the kind of person we are, we try very hard to think like people like us are supposed to think.

For all the explanatory power of this model, however, it is almost impossible to convince anybody that it is true. Most Americans sincerely believe that they are independent thinkers who study issues carefully and make up their mind by assessing true facts in the light of their deeply held values. Nobody wakes up in the morning and says, “today, I am going to align my core belief system with the collective hive mind of a political party.” Most of us would be deeply offended if anybody suggested that we did.

But in-group/out-group thinking is embedded deeply into our fundamental cognitive architecture. Whatever we may think, we know, as a matter of pure instinct, that our survival depends on the good graces of whatever tribe we happen to belong to. If we disagree with our tribe, we are much more likely to change our mind or suppress our disagreement than we are to find a new tribe. And even if we do find a new tribe (or a new party, ideological label, or whatever), we are likely to begin immediately to conform ourselves to the ideologies it espouses.

Genuine independence of thought is only a few hundred years old. It may be possible for brief amounts of time with extremely great effort, but it is rarely a match for six million years of evolutionary instincts telling us not to try to face the world alone.