3 of 3

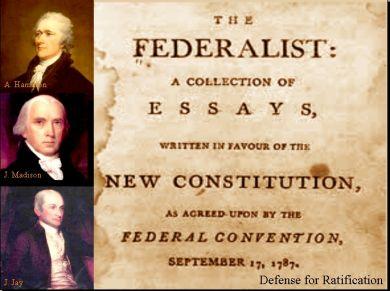

“Extend the sphere, and you take in a greater variety of parties and interests; you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common motive to invade the rights of other citizens; or if such a common motive exists, it will be more difficult for all who feel it to discover their own strength, and to act in unison with each other.”—James Madison, Federalist #10

In my last two posts (here and here), I explored the problem “partisan sorting”—the movement in the American electorate from two ideologically mixed parties in the 1950s and 1960s to the current system of two ideologically “sorted” parties where nearly all liberals are Democrats and nearly all conservatives are Republicans. Research shows that, once partisan sorting occurs, voters and parties become more extreme, more polarized, and less willing to compromise with the other team.

As I have tried to show, there are two underlying causes to partisan sorting: one that we can’t do anything about, and one that we could address quite forcefully with a solution that has been around for 225 years.

The thing we can’t do anything about is human nature. We are accustomed by millions of years of evolution to think in terms of our tribe ("us") and not-our-tribe ("them"). Thus, we immediately characterize people who disagree with us morally or intellectually inferior, and we strike out viciously against anybody we perceive as a threat to ourselves or our in-group. We adopt beliefs for reasons that have nothing to do with logic or rational thought, and we exhibit an overwhelming conformation bias towards information that supports whatever we happen to believe. We pretty much suck at civility. And there is not much that anybody can do about any of this.

James Madison understood these aspects of human nature very well, and he used them as the basis for some of his most important political insights. The best of these occur in Federalist #10—Madison’s first, and most enduring, contribution to the essays written to support the Constitution. The focus of Federalist #10 is what Madison called “the violence of faction,” or the tendency of free people to divide into interest groups, or “factions” that, if not carefully managed, can destroy democracy.

Madison believed that factions were potentially so dangerous to a republican government that “the regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation.” Yet he also understood that there was no way to suppress political factions without destroying freedom. What an enlightened government must do, therefore, is find a way to control their effects.

And this is where he hit upon his greatest insight. Since factions cannot be minimized, Madison reasoned, they should be maximized. The government, then, should do everything possible to encourage the development of multiple parties and interest groups. The competition between these multiple groups will prevent one or two of them from ever dominating the political process. To be effective within a great multitude of voices, different parties will have to constantly form, dissolve, reform, and compromise as new issues come to the forefront.

A government would not have to do much to make Madison’s system work. All it needs to do is refuse to incorporating any party or interest group into the political system and give every faction an equal opportunity to form and be heard. In practice, this would mean

- Neither the federal nor the state government would subsidize interparty competitions, such as primary elections or allow them to be conducted on the same ballot as genuine electoral business.

- Where primary elections were necessary, they would be conducted independently of political parties. The top two vote-getters would advance to the general election with no regard for party affiliation.

- Voters would never be required to declare a party affiliation to vote in any state-sponsored or state-affiliated election.

- No political party would ever be given a guaranteed spot on a ballot. Nor could previous election performance be used to determine ballot eligibility. Whatever standards used to govern ballot access (signatures, filing fees, whatever) would apply regardless of party affiliation.

- Party leaders (minority leader, minority whip, etc.) would have no official role in legislative bodies. They would not be empowered by the chamber rules to advance, or prevent, legislation.

- Political parties would be treated approximately the way that religious groups are treated: the government could neither help nor hinder their progress and could do nothing to take official cognizance of their existence.

This is roughly the state of affairs that Madison and most of the other framers imagined in 1787. There were no political parties at the time, nor was the Constitution even capable of handling them when they did emerge (as the electoral tie of 1800 demonstrated). Madison foresaw them, of course. And he understood that it was inevitable that they would form.

What was not inevitable, though, is that there would only ever be two parties at a time—that all of the regional, religious, economic, ethnic, and other interests that Madison foresaw would be shoehorned into two permanent coalitions that would become more and more institutionalized at the same time that they became less and less diverse. Such a situation, in fact, might be the only way to undue the Constitution’s well-designed safeguards against both majoritarian tyranny and paralytic dysfunction.

Stop me when any of this starts to sound familiar.