In a recent discussion about privacy and metadata, a good friend of mine—who is also a judge and is in the habit of issuing search warrants—highly recommended that I read my cell phone user agreement carefully. I did, and this is what it said:

We may provide Personal Information to non-AT&T companies or other third parties for purposes such as:

- Responding to 911 calls and other emergencies;

- Complying with court orders and other legal process;

- To assist with identity verification, and to prevent fraud and identity theft;

- Enforcing our agreements and property rights; and

- Obtaining payment for products and services that appear on your AT&T billing statements, including the transfer or sale of delinquent accounts to third parties for collection. . . .

- We may share aggregate or anonymous information in various formats with trusted non-AT&T entities, and may work with those entities to do research and provide products and services.”

Hmmm. I kind of see what he was getting at. Not only can my cell phone provider give this information to the government without a search warrant (since I have already consented by signing the user agreement); they can give it, trade it, or sell it to pretty much anybody for any reason because it is their stuff. This, it turns out, is part of what I agreed to when they gave me a .99 cent i-Phone and a few 1980s hair-band ringtones.

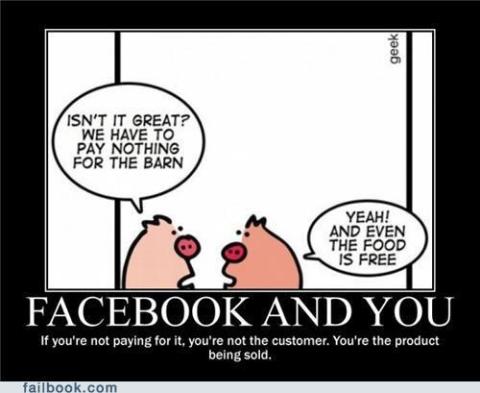

Facebook has an even broader clause in its user agreement in which, in exchange for being able to play with my friends, I grant them “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that [I] post on or in connection with Facebook.” As anyone who spends time on the Internet knows, or should know by now, if you are getting it for free, you are not the customer; you, and your data, are the product.

These are the realities of the world of big data. A month before Edward Snowden set off a national panic by revealing that Verizon gives cell phone data to the government, the Wall Street Journal reported, and nobody else noticed, that the same company had been selling the same data to to other companies since October of 2012. This is just how it works. Whenever I post something to Facebook, search for something on Google, buy something at Amazon, or make a call on my cell phone, I am creating valuable data that these companies will take possession of and sell over and over again. And usually, this is all in the “user agreement” information that I never really read but always check the box saying that I did.

So, as outraged as we may be that the government somethingorother did some thingie-thing that we do not approve of with our meta-data-y stuff, all we have really lost are two comforting illusions: 1) that our data was ever private, and 2) that it belonged to us to begin with. It wasn't, it didn't, and the federal government is only a bit player in the data-mining game that our corporate overlords have been playing much more successfully for years.

In practice, this creates a genuine dilemma for the purer libertarians among us. If we are serious about preventing the government from snooping in our metadata, we are going to have to get a lot more comfortable regulating a major corporate profit center. There is just no way to prevent our government (or any other government for that matter) from ending up with data that is freely sold to any pizza chain, shoe manufacturer, or time-share condo company who can afford to buy it.