To true believers, both communism and capitalism are immune to historical critique. Tell a group of devout Marxists that communism has failed wherever it has been tried, and they will respond that it has never been tried. The “so-called communist societies” of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, they will say, were nothing like the pure Worker’s Utopias that Marx imagined.

It works about the same way with die-hard free-market types. Point to the abusive Industrial Revolution societies of 19th century England and America, and they will respond that these were nothing like a real free market. They will use words like “corporatism” and “cronyism” to describe these pale imitations of the capitalist ideal. If we just allowed the markets to be free, they tell us, all of our problems will fade away.

Both positions end up saying the same thing: that if a pure ideology could just operate without the constraints imposed by history and reality, it could produce, if not a perfect society, at least a very good one. But this is the opposite of how things actually work. Responding to the constraints imposed by history and reality is what governments are supposed to do. “Sticking to an ideology,” as it turns out, is the opposite of “governing stuff.”

This is not to say that communism and capitalism are equally good starting places for a society. They are not; capitalism wins hands down. Free markets are much, much better than command economies at things like incentivizing production and facilitating distribution. But we should understand why this is so. It is not because communism is evil and capitalism is holy; rather, it is because the core assumptions of the free market system—that people are basically selfish and will almost always pursue their self-interest at the expense of other people or society in general—align almost perfectly with human nature.

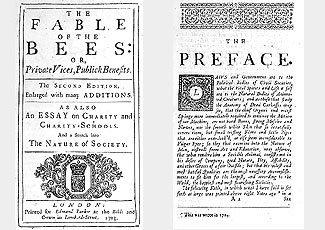

One of the first Europeans to understand both the power of the free market and its fundamentally amoral nature was the Anglo-Dutch poet Bernard Mandeville. In 1705—seventy years before Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, Mandeville wrote his most famous poem, “The Fable of the Bees”—one of the world’s great parables of free-market capitalism.

Subtitled “The Grumbling Hive,” Mandeville’s poem tells the story of a hive of selfish, vice-ridden bees who all seek their own pleasures and, in the process, become an enormously productive society:

Thus every Part was full of Vice, Yet the whole Mass a Paradice; Flatter'd in Peace, and fear'd in Wars They were th' Esteem of Foreigners, And lavish of their Wealth and Lives, The Ballance of all other Hives. Such were the Blessings of that State; Their Crimes conspired to make 'em Great; And Vertue, who from Politicks Had learn'd a Thousand cunning Tricks, Was, by their happy Influence, Made Friends with Vice: And ever since The Worst of all the Multitude Did something for the common Good.

This goes on until a do-gooder bee ruins everything by convincing the bees to abandon their selfish ways and concentrate on the common good.Without selfishness to motivate them, they lose the desire to work. Without luxuries to pursue, the producers of luxury items have no work to do. Saved from everything that made it evil, the bees lose everything that made them great.

Mandeville gets it about right: free markets work, and work very well, because they appeal to the concerns that motivate us and not to the values that inspire us. If we fail to understand this, we run the risk of attributing a positive moral value to something that is really just a very useful set of tools.

And in this case, the difference between a moral principle and a useful tool could not be more important. Moral principles belong to ideologies. By their very nature, they must be rigid, absolute, and uncompromising. Tools, on the other hand, are for pragmatic managers. We can use them when, and to the extent that, they give us real solutions to actual problems. And we can use other tools to solve other problems.

This is why every society that anybody wants to live in today mixes a free-market economy with some centralized redistribution of wealth and income. There are outliers of course, such as the great worker’s republic of North Korea and the free-market paradise of Somalia. The rest of us just argue over percentages and pretend that we are taking moral positions when we are really just trying to figure out the best way to use our tools.