With all eyes on Europe as France and Spain struggle to close their budget deficits while global markets anxiously wait for a final Greek exit to put a hole in the Eurozone, things seem quiet on the fiscal policy front here in the United States, but brewing under the surface is another big fiscal fight over the national debt, yearly budget deficit, and the debt ceiling.

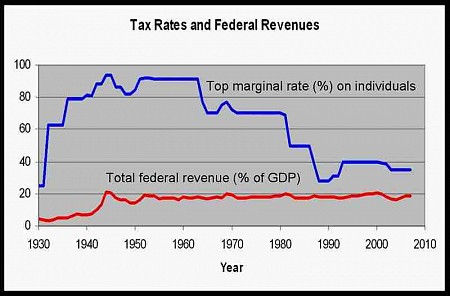

One relevant principle in economics is the observable phenomenon that increasing tax burdens hinder an economy's outputs. In 1913, passage of the 16th Amendment permanently embedded the income tax into our lives, but the seemingly counter-intuitive inverse relationship between taxation rates and tax revenues ever since is well documented. Regardless of marginal rates, tax revenue as a share of GDP remained static in a narrow range of 18-20%, even in the 1960s when the top marginal tax rate was 90%:

These are interesting figures for a nation founded on resistance to unpopular taxes. At the Wall Street Journal, W. Kurt Hauser summarizes: "Tax revenues as a share of GDP have averaged just under 19%, whether tax rates are cut or raised. Better to cut rates and get 19% of a larger pie." If we eliminate the cable news, split screen, partisan mentality from the equation and focus on the numbers, it becomes apparent that we just can’t tax our way to a balanced budget. Economist Antony Davies explains:

“[T]he richest 5 percent of Americans already pay a tax rate almost three times higher than the average tax rate of the remaining 95 percent. It’s hard to argue that the richest aren’t paying a fair share of taxes. Aside from that, for the richest Americans to shoulder the deficit, we would have to raise their effective tax rate to 88 percent. At 88 percent, a family earning $300,000 each year has only $36,000 after taxes—less than the average American earns.”“The budget deficit is so large that there simply aren’t enough rich people to tax to raise enough to balance the budget.”

Moreover, even if we could eat the rich, the accumulated windfall tax revenue would still end up in the hands of bureaucratic central planners under the false pretense that a single planner can act as an architect of the economic activity of millions of market actors. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), the founder of modern economics as we know it, Adam Smith describes this behavior by a “man of system”:

“[Such a man is] apt to be very wise in his own conceit; and is often so enamored with the supposed beauty of his ideal plan of government that he cannot suffer the smallest deviation from any part of it.”

Economist James Otteson explains Smith’s “man of system”:

“The man of system faces a problem: individual people are not chess pieces to be moved only under someone else’s authority. Individuals make their own decisions and move on their own. When individuals are constantly butting up against demands from the government that they find imposing or contrary to their desires, Smith says, ‘society must be at all times in the highest degree of disorder.’”

But again, our history of marginal tax rates and total federal revenue as a percentage of GDP shows that rather than focus on taxes and revenue, getting the fiscal house back in order requires a sober assessment of the bipartisan spending problem. An intellectually honest dialogue about entitlements, a third rail of American politics, must occur at the national level. In their current structure, spending on programs like Medicare and Medicaid will engulf the budget in the next couple of decades. Any expectation of receiving future benefits from these programs requires serious, immediate cuts.

Mathematically, this perpetual runaway spending is simply not sustainable. No level of taxation will be able to keep it going, as the data above show.