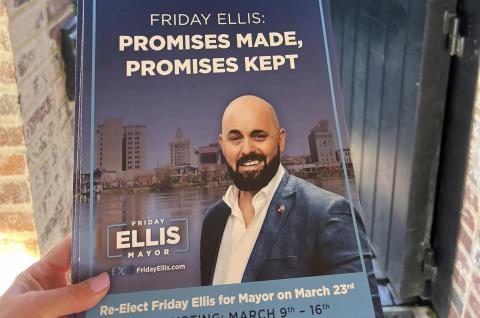

Photo Source: Friday Ellis Facebook

In city governance, partisanship and demography need not be destiny. Ask Friday Ellis.

Concerning his initial election in 2020, Monroe, Louisiana independent Mayor Ellis could have been written off as a fluke. He defeated nearly two-decade incumbent Jamie Mayo, who like 64 percent of the population is black and like 54 percent of the electorate is a Democrat.

Detractors accused Mayo of increasingly becoming detached from governing the city of around 48,000 that is the urban hub of 12 northeast Louisiana rural and agriculture-based parishes (counties). It's a city with a history of racial divisions not the least symbolized by a heavily white residential concentration in the northern part of the city offset by an equally high concentrated black population in its south.

Four years ago, Ellis, a businessman and former mid-level city employee, cast few aspersions on what caused Monroe’s ailments during his campaign, whether it be feelings of separateness among its citizens, its declining population, or its recent stagnant economic growth, or as consequences of Mayo’s rule. Instead, he laid out a future vision focusing on what he would pursue in the provision of basic city services – public safety, drainage, trash collection – and efforts he would make to jumpstart economic development to benefit all citizens.

He won enough converts to defeat Mayo and two other Democrats and a Libertarian without a runoff election. (In Louisiana state and local elections, all candidates regardless of party affiliation run together and if none secure a majority the two highest finishers engage in a runoff.)

Supported by area Republicans and conservatives – with his wife Ashley already an elected Republican member of the state’s Board of Elementary and Secondary Education -- it was tempting at the time to write off his win as a referendum on Mayo and Ellis positioned as the only serious challenger.

He spent the next four years proving this assertion wrong.

Ellis adopted a highly consumer-focused approach on governance. His administration went out of its way to gather citizen input, from complaints to aspirations, rather than impose ideas as a guide to policymaking, believing that the community will let you know what it wants.

He instituted “Fridays with Friday” where he personally solicited input from residents, and if a matter involved some kind of casework after attempted resolution, he surprised residents on some occasions by showing up at their front doors asking whether the problem had been resolved.

Recognizing that despite his win he needed to cement support to govern effectively, he eschewed pursuit of potentially divisive ideological issue preferences and focused on an agenda that unified residents around improving services and initiatives designed to spur economic development. He also cajoled a city council with a 3-2 Democrat majority to support this -- using it to build trust.

Perhaps most importantly, he asked residents to “shed the cloak of apathy” – an attitude that little could be done to address Monroe’s problems – and believe his bottom-up approach could yield results. This proved helpful with successful business outreach efforts.

Ellis paid particular attention to the southside through a mixture of official and unofficial actions. He launched significant, long-desired capital projects, in the process ameliorating a conflict with a quasi-independent state agency established to provide economic development for the area.

He used the bully pulpit to draw in new businesses that addressed residents’ basic needs such as eliminating what had been a food desert. He also renewed attention to crime control (Monroe still has one of the highest per capita murder rates in the country, but crime rates have gone down more than the statewide average since Ellis took office).

This spring, in his re-election campaign facing Mayo and another black Democrat, Ellis highlighted his record and kept to the issues but not ideologically so, refraining that all citizens wanted the same things. This resulted in capturing 63 percent of the vote -- an increase of ten percent from 2020.

He ended up defeating Mayo in a few majority-black precincts and polling showed even a significant portion who voted against him held a favorable view of his term.

Relentless prospective engagement with the citizenry and a commitment to responsiveness that focused on issues commonly concerning citizens melted away racial and partisan divisions that led to his re-election. It’s a model that politicians who on the surface wouldn’t seem to fit their constituencies should study for campaigning and governing success.

About the Author: Jeff Sadow is an associate professor of political science at Louisiana State University Shreveport. He is a frequent media commentator on state politics, and writes opinion columns about Louisiana politics, a blog about Louisiana government in general, and another during sessions of the Louisiana Legislature concerning bills it considers.