Disagreement is critical to the well-being of our nation. But we must carry on our arguments with the realization that those with whom we disagree are not our enemies; rather, they are our colleagues in a great enterprise. When we respect each other enough to respond carefully to argument, we are filling roles necessary in a republic.—US District Judge Thomas B. Griffith, “The Work of Civility”

The election of 1816 supposedly solved the problem of political factions for good. Ever since George Washington’s first term, the republic had been buffeted by partisan storms. In the Federalist Papers, both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison had warned the new nation against splitting along party lines—and then both went on to start political parties that split people along party lines. As the first Treasury Secretary, Hamilton became the leader of the Federalists, while Madison joined with Jefferson to create the party then known as the Republicans.

But the election of James Monroe in 1816 was supposed to bring an end to all the partisan squabbling. It was the beginning of the “Era of Good Feelings.” The nearly defunct Federalists did not even field a national candidate, and Monroe won without breaking a sweat. Finally, the scourge of faction had been overcome, and the nation could get down to the business of agreeing about things.

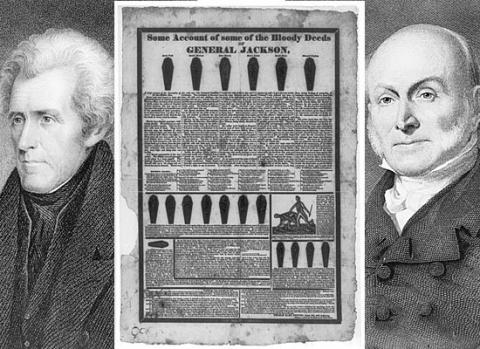

It didn’t last, of course. The victorious Republicans soon split into two extremely factious groups: the “Democratic Republicans” under Andrew Jackson, who became "Democrats," and the “National Republicans,” under Henry Clay, who became “Whigs,” borrowing the name of the British anti-Monarchy party in an attempt to portray Jackson as a tyrant. Slavery and sectionalism soon entered the picture, and, the period between 1824 and 1860 became the most contentious, partisan, factionalized period in American history.

All of this is just another way of saying that political partisanship has always been about as bad as it is today. It is just about as depressing to read a newspaper or listen to a talk radio program in 2013 as it is to read a history book about, or a primary source from, the election of 1828, which (in my book) still holds the record for ugly, mean, negative campaigning.

And yet, I really do believe that we can do better. Given the fact that we are human beings with different experiences and predispositions, we are probably never going to agree with each other. That is quite all right. We aren’t supposed to. But I hold out hope that we will be able to try to understand each other—and to actually engage in political debate rather than in the sequential shouting and mutual recrimination that most of us mistake for arguing. This has not happened a lot in American history, but it has happened often enough to prove that it can be done if we try really hard.

As I read contemporary political commentary, I see most of today’s political divisions occurring between two contrasting views of the proper role of government in a free society. We can label these positions “liberal and conservative” or “libertarian and communitarian,” or anything else we like. They are essentially the same things that divided Federalists and Republicans in 1796 and Whigs and Democrats in 1840. Both of them are rational, internally consistent, morally defensible, and fully consistent with the Constitution. And they are both positions that reasonable, intelligent people can hold, advocate for, and disagree about, while remaining friends.

To the best of my ability to summarize these positions neutrally, they go like this:

Position A: Government is a necessary evil that should exist but should be limited to providing only the few basic services that people cannot provide for themselves, such as military and police forces, judicial bodies, laws, treaties, and some interstate infrastructure (roads, bridges and the like). What people can provide for themselves—health insurance, higher education, retirement savings, transportation, etc.—they should provide for themselves. The State should not interfere with people’s rights to defend themselves and their families, and government should let us keep as much of our own money as possible so that we can spend it as we see fit and not as the government sees fit to spend it for us.Position B: Government is an instrument through which people come together to create the kind of society that they want to live in. The government, then, is an extension of the popular will that can, and should, incorporate the values of the community. Care of the poor, the vulnerable, and the weak has always been one of the essential functions of a society, and government, as an agent of society, is a logical vehicle to accomplish this function. It is unfair to set the ground rules of a society in such a way that some people can accumulate hugely disproportionate amounts of wealth while others do not have basic necessities. Both taxation, and some limits on absolute liberty, are the price we pay to live in a civilized society.

You may say I'm a dreamer, but. . . what would happen if we stopped pretending that the other guys are stupid and instead started talking about the relative strengths and weaknesses of each position—and, here is a tip: they both have strengths and weaknesses.

Once we acknowledge that people who disagree with us are not actually stupid, evil, tragically misinformed, or bad Americans, we can try to learn enough about each other to have arguments—not in order to destroy each other or even to persuade each other all the way, but to clarify where we disagree and perhaps learn something in the process.