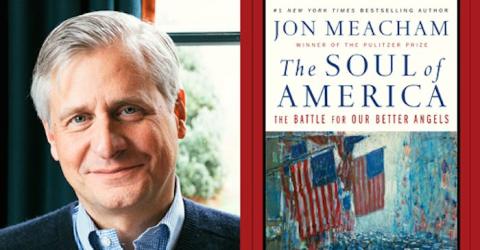

Here’s a passage that brings historians’ public value to life: “The only way to come to understanding is by knowing the history that has shaped us,” writes Jon Meacham in his evocative, The Soul of America (p. 259).

What Meacham asserts is profound. What appears to be new in America’s politics is often anything but. A more likely description, Meacham contends, is that it’s the newest episode of ‘America’s eternal struggle.’

“I’ve wondered why the next generation can’t profit from the generation before,” Meacham quotes a flummoxed Harry Truman. “But they it never does until people get knocked in the head by experience.” (p. 259)

So true: Live it and know it. But let’s wish it were otherwise. If Americans could actually learn from history and practice accordingly—especially now, living as we are, in the Age of Trump—we’d be so much better off as a nation.

But they don’t. And that’s what makes this book so important: Meacham tells many Americans ‘what they never knew.’

If history were truly our guide, then each and every time we scream—“Trump! There he goes again! –we’d appreciate what may be the most poignant passage of Meacham’s book: “And yet and yet—there is always an ‘and yet’ in American history.” (p. 103, bolding added)

America’s script, Meacham argues, is a constant yin and yang—of taking two steps forward (sometimes one) and one step back (sometimes two). He describes it as “the war between the ideal and the real, between what’s right and what’s convenient, between the larger good and personal interest” (p. 7).

Each American president engages in that very same struggle. For example, LBJ exerted moral leadership when he signed The Civil Rights Act—knowing full well that he was likely signing over the South to the Republican Party. Richard Nixon showed a very different temperament—and paid a steep price—when he conspired in Watergate.

Then there was Andrew Jackson, the president who took a Hobbesian view of the presidency (that is, every single day is a war). Jackson, whom Meacham describes as “the most contradictory of men,” ”spoke passionately of the needs of the humble members of society…and made the case for a more democratic understanding of power.” But he (also) “massacred Native Americans in combat, executed enemy soldiers, and imposed martial law” (p. 29), while constantly blaming others and expressing self-pity with regularity.

I’ve come to see Woodrow Wilson—once my presidential hero—in that contradictory way, too. Wilson led America during the era of suffrage triumph and argued vociferously for what eventually became the United Nations. But he also squelched free speech through The Sedition Act (1918) and was adamant about keeping African Americans out of government (they don’t have ‘the intelligence,’ he surmised).

Thank goodness we had activists then (as we have today) that got into Wilson’s face and fought him every step of the way. Alice Paul (my new hero) is one example.

But neither Jackson nor Wilson—add Nixon to that list, too—was a one-off. “If we expect trumpets to sound unwavering notes,” Meacham observes, “we will be disappointed. The past tells us that politics is an uneven symphony” (p. 103).

Consider this: for all the great things FDR did for America, keep in mind that he interred Japanese-, German-, and Italian-Americans during WWII. And he wouldn’t support anti-lynching legislation—despite Eleanor’s constant urging—concerned that he’d lose Congressional votes for his New Deal.

Of course, many of us would trade Wilson or FDR for Donald Trump in a heartbeat. Trump—an extreme version of the losing side of what Jon Meacham calls, “the battle for our better angels”—is the reason he wrote this book: “I am writing now,” Meacham scribes, “not because past American presidents have always risen to the occasion but because the incumbent American president so rarely does,” p. 13).

But staying true to the theme of this important book, Meacham doesn’t see Trump as unique. In many ways, he’s a 21st Century version of that damnable 20th Century figure, Senator Joe McCarthy.

It’s a valid comparison, too. “Our fate (as a society) is contingent upon which element—hope or fear—emerges triumphant,” Meacham writes (p. 7). Lincoln and Obama exuded hope. McCarthy and Trump peddled fear. That’s why—to better understand Trump—it’s advisable to learn more about McCarthy.

“He (McCarthy) exploited the privileges of power and prominence without regard to its responsibilities,” Meacham writes. “A freelance performer who grasped what many ordinary Americans feared,” McCarthy knew that “the country feared Communism…and he fed those fears…. A master of false charges, of conspiracy-tinged rhetoric, McCarthy could distract the public, play the press, and change the subject—all while keeping himself at center stage.” (p. 185)

Sound familiar? Well, there’s more. Even after McCarthy was disgraced publicly, polls showed that 34% of Americans still supported him (p. 201). And McCarthy’s primary advisor—Roy Cohn—later advised a young, New York real estate developer … named Donald Trump (p. 206).

What does Meacham’s work mean for independents? For an answer, I recommend reading the book’s conclusion, “The First Duty of an American Citizen” (p. 255-272). In it, he offers a recipe for response—and two of five ingredients speak directly to what it means to be Independent.

Respect facts and deploy reason: Being able to uncover facts, weigh facts, and come to a reasonable conclusion requires cognitive skills and stick-to-itiveness. It also requires the capacity to disassociate claims from claimants, especially claimants who masquerade as Pied Pipers. To do otherwise, Meacham writes, “is to preemptively surrender the capacity of the mind” (p. 268). The take-away message: think independently.

Resist tribalism: “Wisdom generally comes from a free exchange of ideas, and there can be no free exchange of ideas if everybody on your side already agrees with one another,” Meacham observes (p. 268). Put another way, ‘following the party line’ has costs—not only in terms of constraining the idea pool, but by infecting the public domain with (what I call) the politics of affiliation. To wit: you must go along to get along, especially if you want to get ahead in the party. The take-away message: act independently.

The bottom line is that Jon Meacham’s book is an important read—especially today. Yes, today is probably another chapter in what Meacham calls our ‘eternal struggle,’ but it’s an especially ornery one. To address it effectively, we must learn from the past. But that’s no small order in a society where a lot of folks don’t read much or at all; don’t engage in multifaceted political dialogue much or at all; and get a good share of their news (if not all of it) from friends, social media, and 24-hour ‘news’ networks.

Sadly, there isn’t a lot of depth, understanding, and perceptivity across America today. That makes it easy for the public to be duped, and duping opened the door for Donald Trump.

But duping doesn’t serve democracy—not the kind the Founding Fathers had in mind; not the kind you embrace; and not the kind America needs to be that “Shining City on the Hill” Reagan referenced during his valedictory (1989).

It would be a mistake, though, to conclude that the character of our nation rests solely—even primarily—on the back of the person in The White House. Meacham, among others (Ralph Waldo Emerson, too), believes that it rests with the character of the people (p. 40).

Character. Leading for the public good.

The time is now. The stakes are high. There aren’t alternatives, Eternal Struggle or not.