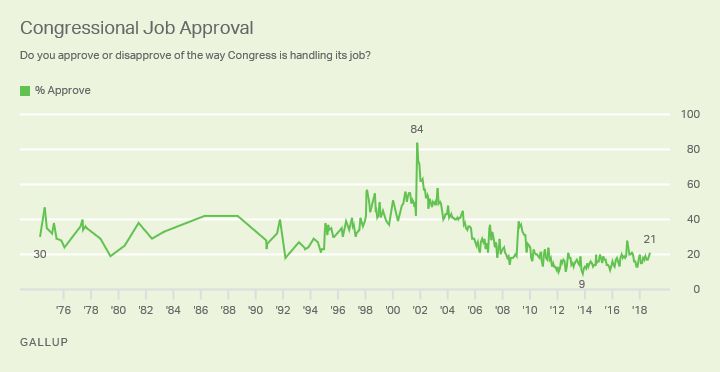

Congress has had abysmally low approval ratings– which have averaged well below 40%– since the 1970s, years before the first millennial was even born yet. Since 2008 Congress' approval ratings have averaged below 20%, dipping as low as the single digits.

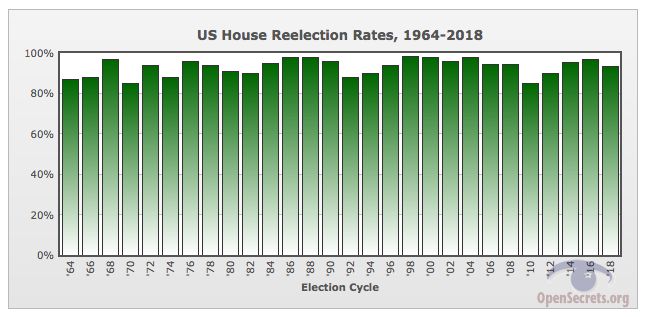

Yet paradoxically, according to OpenSecrets:

"Few things in life are more predictable than the chances of an incumbent member of the U.S. House of Representatives winning reelection. With wide name recognition, and usually an insurmountable advantage in campaign cash, House incumbents typically have little trouble holding onto their seats—as this chart shows."

It may very well be the case that popular, reform-minded candidates have too much in common with third party and independent candidates, who are invariably anti-establishmentarian, and these "minor" candidates split enough votes from challengers to keep incumbents in their seats for another two years– or six years in the case of U.S. Senators.

In a scenario like this, even though more voters prefer the challenger to the incumbent, the traditional "choose one" system of voting "spoils" the result by forcing some voters to choose between a compromise vote for a major party challenger and a "pure" or "principled" vote for a third party or independent candidate.

The media refers to these minor candidates (like Ross Perot, The Reform Party's presidential candidate in 1992, or Ralph Nader, the Green Party's presidential candidate in 2000) as "spoilers," but it would be more accurate to attribute vote spoiling to the "choose one" system of voting itself. By changing the system to a more sophisticated one, ranked choice voting advocates say we can get results that more accurately reflect more of the electorate.

In one form of ranked choice voting called Instant Runoff Ranked Choice Ballots, voters rank the candidates in order of preference, and if their preferred candidate gets fewer votes than the rest, their vote will count toward their second choice in an automatic runoff.

If that candidate is eliminated in the second round of tallies, then their vote counts toward their third choice, and so on… until a winner is selected who has both core and broad support.

This fixes a voting process that in most places puts voters in a classic prisoner’s dilemma scenario right out of Nobel Prize winning mathematician John Nash’s principles of game theory.

It may be that prisoner's dilemma that results in the confoundingly consistently high congressional incumbency rates, despite consistently abysmally low congressional approval ratings.

Ranked choice voting could change that. And in Maine where it's just been tried for the first time– it is.

In 2018's midterms Maine was the first state to experiment with ranked choice voting for a U.S. House election.

In Maine's 2nd Congressional District, incumbent GOP Rep. Bruce Poliquin received the most votes in the first round of tabulations, but after the instant runoff eliminated last place candidates and awarded those ballots to the voters' second choice, Poliquin's challenger– Democratic State Rep. Jared Golden– won.