On Tuesday morning, the Supreme Court heard arguments for Gill v. Whitford, a constitutional challenge to Wisconsin’s state legislative districts.

The interest in the case was evident by the line for tickets, which started the night before and had wrapped around the block by dawn. I camped out with the crowd of concerned citizens who came from across the country, waiting to see what the Court would do about the problem of partisan gerrymandering.

FairVote submitted an amicus brief in this case and I was eager to see how the justices responded to the issues in person.

For a Supreme Court hearing, Gill attracted a lot of celebrities (by D.C. standards, at least). The Governator himself, Arnold Schwarzenegger was in attendance, determined to “terminate gerrymandering.”

Sitting next to him were several of the plaintiffs from Wisconsin, including William Whitford and Janet Mitchell. (I was fortunate enough to sit between Whitford and Mitchell. A courtroom artist would later produce a picture of Whitford sitting next to Schwarzenegger but left me out, cruelly robbing me of my place in legal history).

In the row ahead of them sat Senator Tammy Baldwin, in the row behind was Wisconsin’s Attorney General. The gallery was filled with some of America’s foremost lawyers, journalists, and political activists.

Most of the justices staked out their positions early.

Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor worried about gerrymandering’s effects on democracy. Breyer was very excited to share his thoughts on a possible gerrymandering test. Chief Justice Roberts expressed concern about the public viewing courts as political arbiters of elections.

ALSO READ: Voting Rights At Stake in Partisan Gerrymandering Case

Alito was skeptical of the research used to support the challenge to Wisconsin’s districts. Gorsuch questioned how courts had jurisdiction over such cases at all, and bragged about his secret, turmeric-based dry-rub recipe (something to look forward to in the next Supreme Court cookbook!).

Thomas, as ever, kept his own counsel.

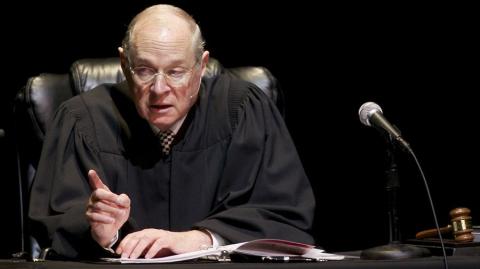

Court observers agree: the four Justices appointed by Democrats will almost certainly side with the appellees while the four appointed by the three most recent Republicans will almost certainly side with the appellants. The real question is what Justice Anthony Kennedy thinks.

Kennedy asked the appellants (who were defending the Wisconsin districts) some pointed questions and remained silent through the appellees’ arguments. (Many commentators saw this as evidence that Kennedy is ready to rule against partisan gerrymandering but their enthusiasm may be premature.

Most of Kennedy’s questions went to whether partisan gerrymandering violates the Constitution, indicating that he believed it did. This isn’t news. Kennedy has already indicated that he sees gerrymandering as a constitutional issue. He was silent on what he thought of the appellees’ proposed standards for finding an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander, which will be the deciding factor here).

Those challenging Wisconsin’s districts explained what was at stake in stark terms. “[D]emocracy will no longer function,” warned appellees’ counsel.

Only the Court can fix the problem since “democracy is about to get worse because of the way gerrymandering is getting so much worse.” But even if the Court sets a rule against partisan gerrymanders, there will still be some serious problems left unaddressed.

Midway through the argument, the Chief Justice suggested that the “partisan symmetry” standard advanced by the appellees was really just an attempt to promote proportional representation.

Not so, argued counsel.

Partisan symmetry focuses on whether parties are equally able to translate votes into seats. (Representation could still be disproportionate, as long as it is equally disproportionate). There was a certain irony in this exchange, given the Chief Justice’s concern that an anti-gerrymandering standard could flood the court with redistricting litigation.

Under a proportional (or “fair”) system for representation, the problem of partisan gerrymandering would largely vanish. Using proportional representation, a party couldn’t win 60 out of 99 legislative seats despite only receiving less than half of the statewide vote, as happened in Wisconsin in 2012.

Success in Gill would be an important victory against partisan gerrymandering but to truly solve that problem, America will have to make some fundamental changes to how it holds elections and those changes won’t come from the Supreme Court.

Editor's Note: This article, written by Dave O'Brien, originally published on FairVote's blog and has been modified slightly for publication on IVN.