Historical perspective can be marvelous for whatever ails you—especially if what ails you is the belief that things are worse in America today than they have ever been. This is almost never true. In the 230 or so years that we have been a country, we have been through—and overcome—a lot. At different points in the past, we have been more in debt, more divided, and more gridlocked than we are now.

And as difficult as it can be to believe when reading the comments section of any online news source in the 21st century, we have been much less civil to each other than we are today. Here are some of the historical moments that I like to revisit whenever I start to think that civil discourse in America has reached its nadir.

The Election of 1800

America’s first partisan election was also one of its least civil. Both of the candidates--Federalist John Adams and Republican Thomas Jefferson--were Founding Fathers and heroes of the Revolution. But the similarities stopped there. Adams had presided over the passage of the lease popular bit of legislation in our brief history—the Alien and Sedition Acts. Jefferson, as the sitting vice president, had secretly written a resolution for the Kentucky legislature authorizing it to nullify the law.

In the minds of Republican voters, Adams was a committed monarchist who planned to reunite with England and set his son up as his successor. In the minds of the Federalists, Jefferson was an anarchist who planned to import the French Revolution to America and set up guillotines on the banks of the Potomac. Neither side believed that the American experiment could survive the election of the other side. Yet, somehow, we did.The Election of 1828

In 1828, there was only one political party in the United States, and it couldn’t agree with itself about anything. The Federalists had been vanquished, and everybody was as Republican. In 1824, John Quincy Adams was elected President by the House of Representatives when a four-way race failed to produce an electoral college winner. When he chose fellow-candidate Henry Clay as his Secretary of State, Andrew Jackson (who actually won the plurality of votes) denounced it as a “corrupt bargain” and spent four years assailing Adams and Clay as undemocratic schemers.

In 1828, these charges became one of the two main issues in the election—the other being the fact that Jackson apparently “married” his wife, Rachel, before she was actually divorced from her first husband. Historians generally call 1828 the dirtiest political campaign ever, and, after it, the Republicans split into two different parties: the Democratic Republicans, who later became simply “Democrats,” and the National Republicans, who took the name “Whigs”—the name of the British anti-monarchy party—because they looked on Jackson as a self-proclaimed King.

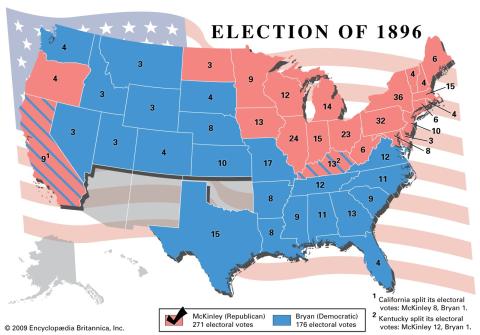

The Election of 1896

In 1896, the most important issue in the United States was the gold standard. Most of the financial sector wanted to keep the anti-inflationary measure in place. Most Midwestern farmers, who were underwater on their mortgages and needed a small amount of inflation in order to survive, wanted a bimetallic standard that included silver in is calculation (and would, therefore, permit inflation of the money supply). The elite of both major parties backed ther gold standard.

But there was a wild and undisciplined faction within the Democratic Party that aligned with called the so-called populist movement. The populist faction captured the Democratic convention and nominated William Jennings Bryan after his famous “Cross of Gold” speech. Mainstream Democrats were horrified that a Yahoo like Bryan could be the party nominee, and they bolted from the party, called themselves the “National Democrats,” and ran former Illinois Senator John Palmer as a third-party candidate.

The election of 1896 pitted the wealthy Eastern elite against the poor farmers and factory workers in the Midwest. Though Bryan was very popular, he faced a divided party and an opponent who raised 3.5 million dollars for the campaign—the equivalent of 3 billion dollars in 2013. McKinley outspent Bryan 5-1 and won one of the most bitter and divisive elections in American history.

America is a great country, and, like all great countries, it has been through plenty of bad things. Many times throughout our history, we have been polarized by partisan politics, intractable positions, regional divisions, and angry factions—just like we are today. But the good times aren’t over over for good. Just as the past was never quite as good as we like to believe, the present is never quite as bad as we like to fear.

Our Constitutional system was built to turn gridlock and factionalism into productive compromises that allow us to move forward. The system keeps getting stuck, but it keeps working anyway. And the bickering, posturing, gridlock, and political theatre are part of the design. Democracy takes time, and turning three hundred million different opinions into a single policy is hard. It is supposed to be hard, and it is supposed to take a while, as it is the trains to dictatorship that always run on time.