We’ve entered an unprecedented era of politicians and commentators who act as self-appointed representatives of “the People,” fighting against the golden-idols who only claim to represent “the People.”

So how can these thought leaders all be so right and so against each other at the same time?

Naturally, we tend to have an elevated sense of self-importance, in part, due to the inordinate amount of time we spend with ourselves.

We ground our principles in our own perceptions; a compound muddled by experience and witness. Attracted to like-minds and directed by a biased guide, our reflection of reality is painted; not photographed.

As a consequence of this self-inflating reality is a sense of righteousness of thought, of conclusion, and of morality.

As a consequence of this self-inflating reality is a sense of righteousness of thought, of conclusion, and of morality.

We live in a world of people, business, hope, despair, and love. Whether we judge people to be good, or love to run deep is largely a measure of the people we know and the love that we’ve experienced; against the particulars being judged.

The same person can be good and bad. The same lover shallow or deep. Depends on who you ask. The wife; the ex-wife; the mistress.

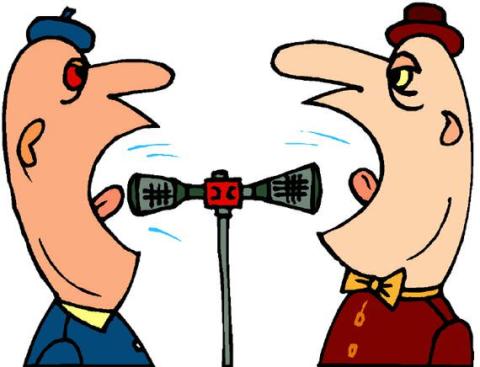

Yet our public discourse tends to speak in absolute terms. Universal goods and bads are applied to people, policies, and their motives as if one perception ruled the world. Our discourse demands a dogmatism that doesn’t reason with real discussion.

This self-righteousness results in discord. There’s no room for compromise when we know the absolute good. Compromise can only taint our perfectly perceived world.

When we admit that we don’t know the absolute good, we lack conviction. We’re undecided. Unable to take a stand. Not fit to participate in the absolute discourse because our words are qualified and our convictions are tempered by recognition of our own fallibility.

We remain silent because we don’t see the absolute good and bad that define the “discussions” of two uncompromising teams. We are governed by a self-righteousness of our own perceptions. Tempered by insecurity.