The British Parliament has determined that the Commonwealth shall not be going to war. David Cameron, though apparently disappointed, appears to be completely bound by the officially nonbinding resolution. The British Prime Minister, who possesses the Constitutional authority to authorize military action, lacks the political support to do so without the consent of the legislature.

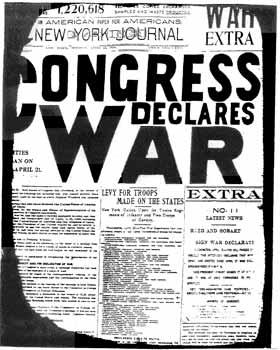

In America it apparently works the other way around. Constitutionally, the President has no power to commit American to a military action. The power to declare war rests entirely with Congress. Politically, however, presidents have been allowed to wage war more or less on their own authority since the end of World War II. Since then, American forces have been committed to wars in Korea, Vietnam, Kuwait, Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq, Lybia, and quite possibly now Syria—without the required declaration of war from Congress.

After the “Vietnam Conflict,” Congress seemed fed up. They passed the War Powers Resolution in 1973, stipulating that the President could not commit troops for more than 60 days without authorization from Congress. It was a nice thought, but presidents have routinely ignored it, and Congress has never really wanted to press the issue.

Even when the House passed Resolution 112.292, reprimanding Obama for leaving troops in Lybia for more than 60 days, they failed to pass a resolution requiring their withdrawal. And, when Representatives Dennis Kucinich (D-OH) and Walter Jones (R-NC) announced their intention to sue the Administration under the War Powers Resolution, only eight other House members joined the suit.

While Congresses love to fuss and fume about presidents who commit the nation unilaterally to armed conflict, the fact is that they have never really been willing to do anything about it. A Congressional majority has never been willing to test the War Powers Resolution in the courts, nor has Congress been willing to issue an actual declaration of War since 1941. As it turns out, the current system of executive-authorized wars works out pretty well for Congress.

Presidents have always been willing to assume extra powers whenever Congress lets them get away with it. Modern presidents have increasingly sought the power to initiate military action quickly and decisively. And both the House and the Senate have been willing to give it to them. It’s easier that way. If it works out well, Congress can bask in the reflected glow of a successful military operation and make a lot of speeches about supporting the troops. If it works out badly (and, more often than not, it works out badly), Congress can call it “the President’s War” and shrug off any political responsibility for starting it.

It wasn’t supposed to work out this way. For almost 75 years, presidents and members of Congress have colluded to shift the power to make war away from the legislative branch of government (which didn’t really want it) and towards the executive branch (which has been more than happy to take it). This has gone on far too long, under too many administrations, and it has now become both practically and constitutionally untenable.

According to a recent poll, eighty percent of Americans think that Congress should have to authorize any military action in Syria. Would that this were 100%--and that Americans didn’t just want Congress to authorize the President’s actions, but to exercise its Constitutional responsibility to determine when and where American military forces are deployed.

Syria is a difficult situation. Both American and humanitarian interests are on the line, and the consequences of both action and inaction are potentially severe. There probably is no good answer, and I honestly do not know what the right response is. But I believe very strongly that the responsibility for making these decisions should not (and according to the Constitution does not) rest with the President alone. The issues need to be discussed, debated, and compromised on in an open forum, where Americans can see their government working and interact with their representatives to influence the process.

These are the kinds of things that Congress is supposed to do. And whether one thinks that we should let them do their job, or make them do their job, it is high time that they do it—and that they force the President, with any means at their disposal, to relinquish the power to make war—a power that presidents were never supposed to have.