In a recent town hall meeting, Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn let it be known that, in his opinion, President Obama is “perilously close to the Constitutional standard for impeachment.” He is wrong. I do not say this to defend President Obama or his administration in any way, but merely to point out something that Senator Coburn should be ashamed for not understanding in the first place: that there is no Constitutional standard for impeachment. The “Constitutional standard for impeachment” is whatever the House of Representatives says it is.

But impeaching a president is something that they, and we, are supposed to take really, really seriously. In the notes to the Constitutional Convention, we see that the two historical figures most discussed when the framers were talking about impeachment were Charles I and Julius Caesar—both of whom were assassinated in revolutions that shook the foundations of their states.

The Framers—and Benjamin Franklin in particular—wanted some way short of murder to remove a chief executive, but they also understood that impeachment was almost as serious a thing as armed revolt. Those who shake the state without really good reasons end up, rightly, paying a steep political price.

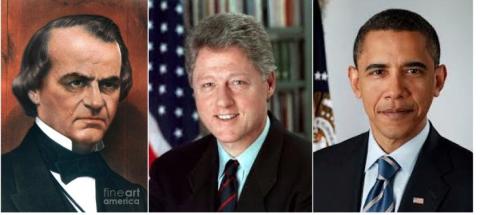

As more and more conservative politicians call for Obama’s impeachment, comparisons to the Bill Clinton impeachment are probably inevitable. But it is really not a very good corollary. For one thing, everybody knew why Clinton was being impeached. And there was credible evidence that he actually broke a law, which, arguably, the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” requires.

The “hey kids, let’s put on an impeachment” mentality we hearing today sounds a lot more like the 1868 impeachment of Andrew Johnson. Johnson was impeached primarily because most of the members of Congress hated his guts. He was a Southerner and a moderate Democrat at a time when radical Northern Republicans controlled both houses of Congress. When the House of Representatives voted to impeach Johnson, they did not even include any charges. They were content to work all of the details out later.

When the charges did come, they were all some version of the complaint that Johnson flouted the will of Congress and unlawfully expanded executive power. But even many of Johnson’s detractors realized that these crimes of interpretation were separation-of-powers issues to be addressed by the courts and not abuse-of-power issues to be addressed by the impeachment process. Eventually, the Senate, by the slimmest of majorities, agreed, and Johnson served out his full term.

The current impeachment drumbeat sounds a lot like it did in 1868. Barack Obama stands accused of exclusively political crimes: delaying the enforcement of the ACA, mandating contraception coverage, expanding executive power and flouting something called “the will of the American people.” But these are the sorts of “crimes” for which we have federal courts, and, ultimately, elections.

But there is a crucial difference between the case of Andrew Johnson and that of Barack Obama: the Congress that impeached Johnson had some chance of success. In 1868, there were virtually no representatives from the Southern states in Congress. Johnson, the only Southern senator who remained loyal during the Civil War, had no natural allies. The removal of the president was actually a political possibility. This is just not the case in 2013. There is no conceivable endgame today in which 67 Senators vote to remove the President.

The current "impeach Obama" movement come from such a perilously weak position--politically, Constitutionally, and legally--that it can only end with the further alienation of conservative Republicans from the political mainstream. The bar for removing a president is a high one; it is supposed to be really hard to undue the results of a national election. And there are real political consequences for causing a national crisis for no good reason and with no realistic chance of success. Republicans who were in Congress during the Clinton era know this well.

The second most important rule of politics and statecraft is "don't shoot at the king." And the first is like unto it: "if you do, don't miss."