(Part 1 of 3)

“During the 1950s and 1960s, most candidates of both parties largely accepted the postwar New Deal consensus—those decades are remarkable for the degree of commonality between the parties.”—Matthew Levendusky, The Partisan Sort, p. 23

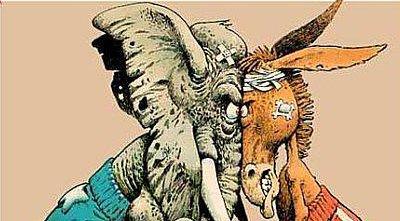

It is common these days to speak of “partisanship” as something that has been getting worse. In many respects it has. The two major parties are much further from each other, and much less willing to work together, than they were in the 1950s or the 1960s—or even the 1980s and 1990s. Most of us cannot remember a time when political partisanship was worse than it is today.

But, as Matthew Levendusky points out in his excellent book, The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans, the bipartisanship that we all remember is really the historical anomaly. Two major parties that fight all the time and don’t get much done is actually the norm in American politics.

This should come as no surprise to anyone who studies history. Very few Americans have ever experienced political trench warfare comparable to what occurred between Federalists and the Republicans in 1800, nor have we seen level of personal destruction that Americans saw in the race between Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams in 1828. And few of us can even imagine the hatred and hostility that, after the presidential election 1860, lead to the immediate secession of seven Southern states and the beginning of the Civil War.

In the 1950s and 1960s, however, things were a lot tamer—not because there were not liberals or conservatives in America, but because there were passionate liberals and passionate conservatives in both major parties. The national electorate had not yet sorted after the transformational presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Liberal Republicans like Earl Warren and Nelson Rockefeller were at the forefront of civil rights and other progressive social movements; conservative Democrats like Strom Thurmond and George Wallace did everything they could to stop them.

But it didn’t last for long. Nixon’s “Southern Strategy” began the process of prying the conservative South loose from the Democratic party—a process that culminated in the Republican Congressional landslide of 1994 and the dissolution of the Democrat’s Southern conservative wing. And the Reagan landslide of 1980 was the beginning of the end for the liberal wing of the Republican party. Since the early 1990s both Democrats and Republicans have become much more ideologically homogeneous on the national level, which has made sorting inevitable in regions that were once much more mixed.

And this sorting has had real consequences. In the first place, sorting has turned tenuous coalitions into hardened ideologies. There is no inherent connection requiring that someone opposed to abortion should also support tax cuts; nor is it logically required that an environmentalist support labor unions. But humans are tribal creatures, and, once we identify with an ingroup (“us”) and against an outgroup (‘them”), we tend to modify a great many of own our opinions to conform to those of our “team.”

Furthermore, in a system where candidates must compete in partisan primaries, sorting feeds on itself to make parties more and more extreme. The more an electorate sorts, the more voters will demand ideologically pure candidates—and the more ideologically pure candidates become, the more sorting cues they will send to the electorate. This self-reinforcing dynamic can move a national party from a fairly moderate position to a radical extreme in just a few election cycles.

Fortunately, however, this system has a built-in mechanism for correction that we see throughout America’s political history: one party or another will invariably become so pure, and so “sorted,” that it can no longer win national elections. This happened to the Federalists in 1800 and to the Democrats in 1860. Both became regional powers (Federalists in New England and Democrats in the South) and were unable to win national elections until they either disappeared (the Federalists) or completely reformed (the Democrats).

At least twice in our history, then, the ideological purity demanded by a sorted electorate has destroyed a great party. It may very well be happening again.