Could we maybe stop pretending that this is an easy question?

Now that we know that the NSA is analyzing telephone and Internet metadata, searching for patterns that might indicate terrorist activity, we are launching into one of those great debates that healthy democracies have to engage in once in a while to remain healthy democracies. Good for us. But let’s make sure that it is a real debate that recognizes the strengths and weaknesses the arguments and the profound complexity of the issues.

Unfortunately, this is not how things appear to be going down. As so often happens in politics, the relevant issues have been simplified into two more or less absolute positions, which go something like this:

Position #1 (mainly taken by the administration): “This kind of surveillance is important to the fight against terrorism. It allows us to detect certain broad patterns of communication behavior that, when pursued further, can help us unravel a terrorist plot. And anyway, we aren’t listening to phone calls or anything; we are just analyzing large amounts of anonymous ‘telephony metadata.’”Position #2 (mainly taken by civil libertarians on the left and the right): “The government has crossed a line and violated the Fourth Amendment by searching through personal data without any kind of warrant or reasonable suspicion. This is a major encroachment of the government into the lives of its citizens. And anyway, this kind of snooping isn’t going to help us catch terrorists.”

It’s the “and anyway. . . .” qualifications that we have to watch out for, as they dangerously oversimplify what are actually very complex questions. This is the disturbing, but inevitable result of a political posture that needs all of its decisions to be easy, clear cut, and free from the need to make difficult trade-offs between partial goods and lesser evils. Unfortunately, it is these partial goods and lesser evils that constitute the bulk of what making decisions usually looks like in the real world.

We should all be willing to acknowledged that there are risks to any decision we make. If we do not mine communications data, we really could fail to prevent a major, destabilizing terrorist attack. Large-scale assaults like the World Trade Center bombings require a lot of coordinating. I for one would be furious if I found out that the NSA could have prevented the 9-11 attacks by mining a lot of anonymous telephone data, and I suspect that I am not alone.

On the other hand, though, we are absolutely correct to worry about what a government might do with access to all of our communications habits—and with potential access to much of the content. Knowledge is power, and this information gives the government a lot of knowledge. As the IRS scandal has recently demonstrated, government agencies with access to a lot of information often do things that they are not supposed to do with that information. The potential for abuse is strong.

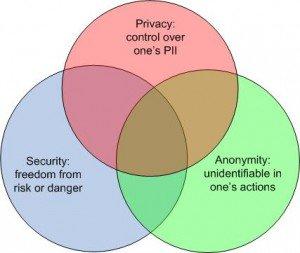

Balancing privacy and security is one of the most difficult things that modern democracies have to do. Because people move freely through our country, we have an extremely difficult time trying to stop bad people from doing bad things. Our computerized communications infrastructure provides a lot of data that can be used to prevent such attacks, but it would be naïve to think that massive communications databases, once constructed, will never be abused.

I do not know what is best. I don't feel like I have learned enough to take a side yet. I am pretty sure, though, that there are no easy, obvious, or painless positions available. This is an actual hard question, and both sides have legitimate and important points to make. We do ourselves and our country a great disservice when we pretend that there is an easy answer.