“The principle that the end justifies the means is and remains the only rule of political ethics; anything else is just a vague chatter and melts away between one’s fingers.” ― Arthur Koestler, Darkness at Noon

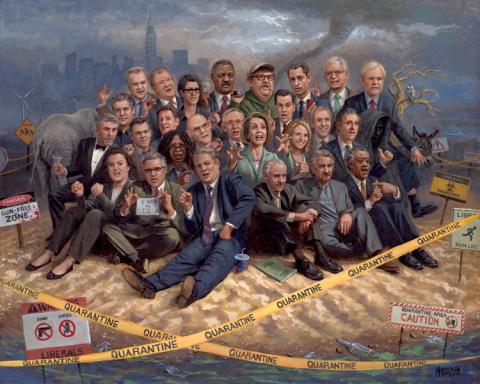

John McNaughton has done it again. The ultra-conservative Utah artist whose previous masterpieces include Barack Obama stepping on the Constitution and Barack Obama burning the Constitution is now auctioning off his newest work, “Liberalism Is a Disease.” And you don’t have to be a Harvard symbologist to interpret the painting's many layers of symbolism. The artist himself does this in an accompanying gloss:

We have a disease. It’s infecting every aspect of our society and it’s time we did something about it. . . . What if we could bring them all together, put them on a desert island and quarantine them for say a hundred years? They believe they have all the answers to everything. But every liberal idea I’ve ever seen has led to total failure. If they were right, their new island home would be a utopia before long. Let’s look at the most liberal communities in the country. New York City, Detroit, Chicago…how are they doing? Yes, I say let’s quarantine them and let nature take its course.

McNaughton’s painting, of course, is a work of fantasy. It is, in fact, a prime example of one of the world's most common fantasies: the fantasy of how wonderful things would be if all of the people who disagreed with us simply stopped existing.

This is related to, but not quite the same as what David Brooks has called “the No. 1 political fantasy in America today” which is “the fantasy that the other party will not exist”—that it will be defeated so handily in the next election that it will cease to be a force that my side will have to reckon with. Brooks correctly identifies this as form of political irrationality that has led to both parties forming non-negotiable policy objectives that do not require the support of the other side.

The McNaughton fantasy, though, is both more common and more insidious. It combines the naive electoral optimism that Brooks identifies with such a certainty of its own absolute rightness—and of the other side’s irreducible wrongness—that it sees the complete destruction of the other side as the only thing that can save bring about the good society.

There is nothing new here, of course. Anybody who has studied the Adams-Jefferson election of 1800 knows that McNaughton-like political fantasy has been with us always. The Federalists in 1800 were convinced that a Jefferson victory would lead to an anarchic reign of terror with guillotines set up along the Potomac. Jeffersonian Republicans, on the other hand, believed that America was just one election away from a restoration of the British monarchy. Both sides were willing to do whatever it took to cure the nation from the disease represented by the other side.

But the partisans of 1800 were as wrong as NcNaughton and other partisans (left or right) are today. And it is a wrongness that does particular violence to the very Constitution that has always played such an important role in partisan fantasies across the political spectrum. The Constitution itself was forged by compromises among partisans who represented a much wider political spectrum than we see today. And they produced a document whose primary function is to bring people with wildly different beliefs together and require them to work together.

There is nothing particularly new or remarkable about McNaughton's newest work of political fantasy. It is as clear a statement as one can make of the governing fantasy of the modern era: that a well-functioning society can only be formed when people believe the correct things--and that, when people persist in believing incorrect things, we must "do something about it."

It is a fantasy that has been anything but idle.