Tell me, ye prim adepts in Scandal’s school

Who rail by precept, and detract by rule,

Lives there no character, so tried, so known,So decked with grace, and so unlike your own? --Richard Brinsley Sheridan, “The School for Scandal”

I’ve learned an awfully lot about Benghazi during this week’s hearings. For example, I now known that

- The attack on the US Mission in Benghazi was a vicious and unpredictable event that could not have been foreseen or prevented.

- The State Department was warned many times about lax security at the US mission in Benghazi and had ample opportunity to correct the problems.

- Soon after the Benghazi attack, the Obama administration lied about its cause and tried to mislead the American people.

- The Department of State did everything that they could to relay correct information to the American people, but, through the fog of war, some mistakes were made.

- The Benghazi cover up was worse than Watergate and may well be the greatest act of executive malfeasance in America’s history.

- Far more diplomats were killed in foreign countries during the Bush Administration, but Republicans never talk about that.

- Hillary Clinton personally held off thousands of Benghazi attackers with only her kung-fu moves and a Samurai sword.

- The Obama administration personally hired Libyans to attack America’s consulate and kill American citizens for sport.

OK, I made the last two up. But just barely. And the rest are more or less direct quotes from politicians and pundits involved in this week’s tremendously entertaining political theater going under the name of “The Benghazi Hearings.”

In all honesty, I must admit that I don’t really understand what happened in Benghazi. And I'm not sure that anybody else does either. The problem is not a lack of intense focus. The problem is that nobody involved in the process has any real interest in discovering the truth. Rather than a serious inquiry into a very consequential failure in American policy, we have two gigantic spin machines, both working from well-tested scripts about how to sustain, or how to diffuse, a political scandal. Finding out what really happened would be an unwelcome distraction for everybody concerned.

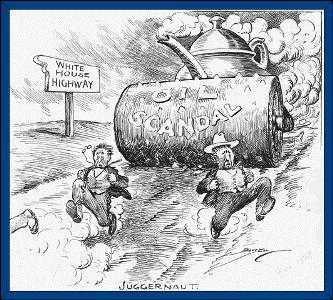

As a result, the Benghazi hearings look and sound a lot like the Abu Gharib hearings, and the Whitewater hearings, and the Iran-Contra hearings, and, well, pretty much every set of congressional hearings I have ever seen or heard. And the public discourse surrounding the event sounds a lot like Teapot Dome (1923), Crédit Mobiliere (1872), and, Henry Clay’s "corrupt bargain" with John Quincy Adams in 1824. The basic moves—attack, defend, hyperbolize, scapegoat, stonewall, and simplify—have not changed much in 200 years.

Except for Watergate, which has become the gold standard of American political scandals, not because it was the worst thing that ever happened, but because it was the worst thing ever caught on tape. And thanks to Richard Nixon's strange obsession with recording every White House conversation he had, The Watergate hearings were the first, last, and only Congressional investigations that ever produced any useful information.

I do not mean to sound ungrateful here. I am enjoying the political theater immensely. In this case, however, we really ought to try to understand what happened in Benghazi—but not so we can run Obama out of town as a craven dictator or cashier John Boehner as a scandalmongering Javert wanna-be. Fixing and avoiding blame are not the most important things for us to do right now. Rather, we need to learn from this tragedy how to do a better job protecting American diplomats in dangerous locations.